Category Archives: Uncategorized

thoughts

Live recital at PS21 Chatham

This August I was very excited to give a live recital at the marvelous semi-outdoor theater at Performance Spaces 21 in Chatham, NY. PS21 put together of series of solo concerts by superb artists, mostly pianists. I was delighted to be on the line-up and play a concert for a sold-out, socially-distanced audience. I played the Bach A minor solo Sonata and “modern classics” by Elliott Carter, Pierre Boulez, and Mario Davidovsky. The video of the livestream is also viewable here. Great review here

About interdisciplinary collaboration

Thanks to the Violin Channel for asking me to write about interdisciplinary arts and my lifelong interest in them!

The page is here and the text is also below:

In first grade, my class was asked to make human figures from colored paper to illustrate what we wanted to do when we grew up.

Enthusiastically, I made three figures and called them a violinist, a writer, and a poet.

I remember drawing and cutting out the figures and outfitting them with clothes and violin and bow, paper and pens.

I had recently begun playing violin and had just written my first short story.

I grew up in a house filled with music and my own life has been centered around music since my pre-teens.

Music is the most mysterious of the arts, sound being invisible yet highly physical, its emotional impact obvious yet its meaning hugely subjective.

Music is made of materials and tools – sounds, rhythms, time, silence, volume – which together communicate and move us in ways we can never totally define.

Since childhood, I’ve kept up writing of various sorts and always been immersed in all the arts, taking in performances, movies, books, visual art, and learning about the artists.

In recent years, I’ve had opportunities to collaborate with a number of wonderful choreographers/dancers, poets/speakers, and visual artists. In my experiences collaborating with, or creating in, different genres, I’ve found it thrilling to combine the bodily senses and steer the imagination to less familiar pathways.

Sometimes artists in other genres work in ways that go on tangents or are more circuitous than I’m used to, and that can be stimulating.

I think what has most intrigued me and affected my work is how blended the art forms actually are.

When we think of putting art forms together, we of course think of opera, or dancing to music, or film with music.

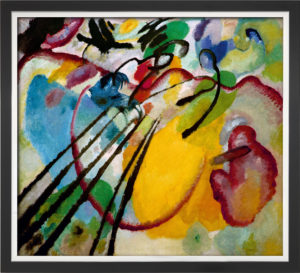

Or we think of musical compositions specifically inspired by another artwork, say a painting or poem.

Besides the ways in which the genres can enhance or inspire each other, I’ve been fascinated exploring the aspects they share.

For instance, playing music involves physical qualities of dance: in the movements we make in response to the music, in playing our instruments and in performing or communicating with others.

Dance is related to acting, in the embodiment of motivations, desires, the gamut of emotions.

Both acting and dance involve a musical kind of phrasing, of timing and inflections.

In music, a performer takes on roles like an actor: I often think of the composer as the playwright whose personality permeates the work, and the composition as the various characters, and maybe narrative, in the play.

Musical composition also can be analogous to ideas in visual art: the use of space/time, repetition, perspective, and so on.

When I study a piece of composed music, I sometimes visualize it as a painting or sculpture, and when I write about music, I go back and forth between the verbal and musical, grappling with the specificities and ambiguities in either genre.

When I’m playing music, sometimes I think of myself an actor or dancer to connect more deeply with the humanity expressed in the sounds.

Heritage and Harmony: Asian musicians

Thanks to WQXR and Donna Weng Friedman for the wonderful project “Heritage and Harmony” and for including me in this celebration of Asian and Asian-American musicians. They asked me to choose a short work by an Asian composer and make a video of it, with a spoken intro about my background. I played “Dramatis Personae” (2016) by Anthony Cheung. He also made a video talking about his piece and the influence of his background on his work.

AMOC in Cultured magazine

AMOC is in the new issue of Cultured magazine. Beautiful article and photos by Emma McCormick-Goodhart and words from several AMOC artists.

Among many things we look forward to is the 2022 Ojai Festival, for which we are collectively the artistic director.

I am also very excited to be working with AMOC on a new production of Luigi Nono’s “La lontantanza nostalgia utopia futura”, with Zack Winkur and my longtime collaborator Christopher Burns. It’s wonderful to have this opportunity to thoroughly rethink and reinterpret the piece both musically and as theater.

.

Colbert Artists Management

I am tremendously honored and excited to have joined the very illustrious roster of Colbert Artists Management. I am looking forward to work with them on future engagements and projects.

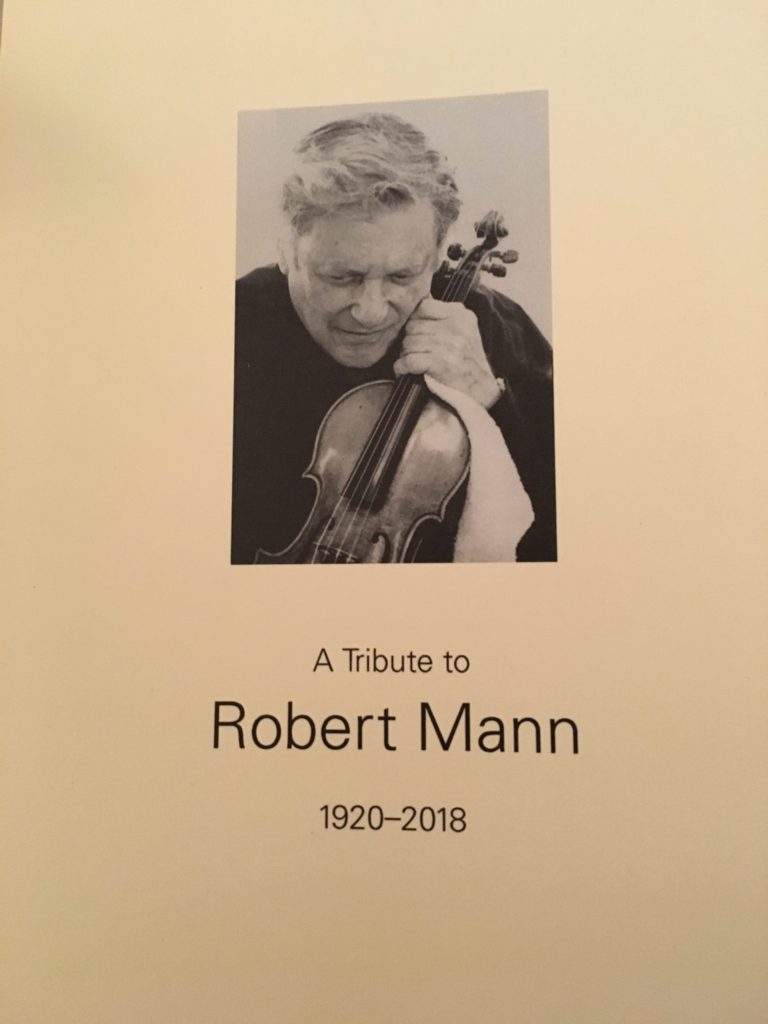

Robert Mann memorial at The Juilliard School

On April 29, The Juilliard School held a memorial for my teacher Robert Mann – founding 1st violinist of the Juilliard String Quartet, American artist, composer, teacher, writer, husband, father. I studied with him for my Masters and Doctorate degrees at Juilliard. After that, I still occasionally went to play for him at his apartment. I also had the great joy to play Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert with him at his family’s annual Christmas parties.

In my life I consider it one of my hugest blessings, and my best luck, to have had a big array and sequence of extraordinary teachers, with each of whom I got to spend a lot of time. In my 20 years at Juilliard (and beyond), these included my violin teachers Shirley Givens and Dorothy DeLay, violinist Felix Galimir, cellist Fred Sherry, and the members of the Juilliard String Quartet. From my childhood, I particularly remember my teacher Rosemary Glyde. My musician parents, Robert and May, have given me continual support, dialogue, and sophisticated feedback. In recent years, composer Mario Davidovsky was essentially a teacher to me, engaging me in rich conversations about music, culture, and the world. And I’ve learned from so many other remarkable musicians and people I’ve worked with. However, of all these numerous influences Robert Mann is the teacher who was my most life-altering inspiration.

His mantra when he founded the Juilliard Quartet was, “Our goal is to play new music as if it had been composed long ago, and to play a classical piece written hundreds of years ago as if it had just been written.” [from his autobiography, A Passionate Journey]

I was tremendously honored and moved to be asked by Juilliard and his family to perform at the memorial, and to play “Rhapsodic Musings”, which Elliott Carter wrote for him in 2001. I remember his happy excitement when he told me, one day at my lesson, that Carter had given him this piece as a birthday present. R.M. stands for Rhapsodic Musings, for Robert Mann, and for the notes Re Mi, which figure strongly in the work. The piece is an amazing, delightful character study of Bobby, his characteristic gestures and personal qualities, both fiery and tender, and a wonderfully concise example of Carter’s brilliant and lyrical music-making.

Ricordi interview about new GF Haas Violin Concerto

Read this interview I did with venerated publishing house Ricordi about the Violin Concerto recently written for me by Austrian composer Georg Friedrich Haas.

Interview with Ethan Iverson

Thanks to Ethan Iverson for interviewing me for his great blog, which is a tremendous resource and repository of thoughts from some fascinating and distinguished musicians. I’ve read many of his interviews over the years and I’m honored to be among them. Read here

Interview in April Magazine

Thank you to April Magazine and Jill Marshall for interviewing me for this article about “embracing the world with violin and viola”.

I’m happy with how the article turned out but thought it would be nice to also share some “outtakes” from our (Oct 23, 2016) email interview:

— Do you prefer playing solo or as part of an ensemble?

I love to play both solo and with others. I would not want to do just one or the other. Violinists are lucky to have some great solo repertoire but it’s been very interesting to me to further explore what the instrument can do and encompass expressively on its own. The thing about playing solo is that you are the one who has to deliver and speak for yourself. You have to do it, no one else can do it for you. I like that situation of responsibility and having to focus on what you want to say and how you can do that. On the other hand, I enjoy the dialogue of playing with other musicians, the reacting to each other, the spur-of-the-moment interplay as well as drawn-out discussions about the work we are doing together. I like to sometimes step back and listen to others and savor the sense of being one strand of a bigger thing.

I feel it’s just as in life – it’s not even a metaphor, it’s the same thing. You need to be alone sometimes, to learn how to both support and critique yourself, how to express yourself and not rely on others. How to listen and think for yourself, not just accept what others around you are saying. On the other hand, you need to be feel part of the group and to understand your role in a larger context. How to have a discussion, how to embrace differences, how to cooperate in an agreed-upon structure. Interacting with a small group, a large crowd, or with one other person – it all teaches you a lot about yourself. It’s also just fun and enjoyable.

— Was the violin a natural choice for you ? Did (do) you play other instruments ?

My first violin was a hand-me-down from my older, Taiwanese-American cousins. So I didn’t actually request a violin but I did take to it very quickly. I always wanted to play my violin as soon as I was home from school. I also play a bit of piano and I like to sing (though my voice got kind of frayed from a bad bout of bronchitis a few years ago).

— Do you remember your very first performance in front of a discerning audience ?

The first performance I remember was at the Hoff-Barthelson music school when I was five or so. I was sick with the flu and my parents said I’d have to miss the concert. But I was so disappointed so they let me play, and I remember being onstage and feeling all hot and feverish but so glad to be playing. The first performance I gave for a discerning audience was probably my audition at Juilliard when I was eight years old. I played a Telemann concerto and the Valse Sentimentale of Tchaikovsky. The teachers were smiling at me when I finished, and I remember my future teacher Dorothy DeLay said to me, “Beautiful music, isn’t it?”

— You travel a great deal. Do you get down-time to explore the towns and cities where you perform ?

I love to travel – not so much the transportation part but visiting new places. Sometimes there isn’t much time to explore – there are rehearsals and concerts and then you have to leave right away afterward – so all you may get to see are the hotel and the hall, and maybe a few other places such as a school or a radio station studio, and the ride to/from the airport! But I love if extra time can be squeezed into a schedule. It’s amazing what you can see in one day. I love to walk around, to see important historical sites but also just to get the feel of the neighborhoods where people live and work. And to go to concerts in other places, to hear the local musicians.

— You’re an Australian-born American with Taiwanese/Austrian/English heritage. Have mixed heritage and vast travel experience brought anything specific to the way you approach creativity and accessibility when making/performing music?

Having a very mixed background has affected my perspective in many fundamental ways, and certainly as an artist. I think it’s given me a basic belief that communication and connection are always possible between different cultures and peoples. It has given me a continual interest in trying to understand where others are coming from and what are the particulars of that culture that they have in themselves. And I think that attitude has carried over into what I do as an interpreter/performer of music: with each piece, I endeavor, as an actor does, to understand the psyche of the composer, wherever he/she may come from and whatever musical language they are using.

Western classical music came from Europe – much of it from Vienna where my grandfather was from – and then spread as an art form to America and other countries of the world. We tend to think of European giants like Mozart and Beethoven as defining “classical music” but classical music has, in the best American spirit of inclusion, now come to involve artistic voices from all over the globe, from every country and ethnicity. I really like to program music by composers from various countries and discuss how their heritage or their world outlook has affected their music – sometimes that’s in an overtly folkloric way, sometimes it’s more subtle or abstract.

Many of us experiment with and partake of different cultures, and wonderful hybrids happen, but I think there will always be a tension between this hybridization and the preservation of cultural identities. That’s causing conflicts but it’s also a huge opportunity to adopt an outlook of respect and try to understand each other, to value those differences and specifics that make each group part of a strong whole. Artists are often in the vanguard of that kind of understanding and exchange, because we essentially deal with personal and universal experience, and communicating that with others.

— When you’re not working through a calendar of events, what kinds of things do you enjoy doing?

I love to take walks and do yoga. I really enjoy an interesting conversation with a friend over a meal or a cup of tea. I love to go to concerts. I have a passion for all art forms. Looking at visual art or a dance piece and understanding what those artists are doing is a great pleasure to me. I can’t draw but I’m very verbal (I started reading very early as a child) and I’m always reading something. Novels, stories, and I am drawn to all kinds of essays and articles online. I like to look around for contemporary poetry that appeals to me. I enjoy cuddling my cat Oski.

American Composers Forum/Liquid Music interview

I’m tremendously excited to perform on the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra’s Liquid Music series on November 14. In anticipation of it, I was recently interviewed by the Minneapolis-based American Composers Forum. Chris Campbell asked some terrific questions – check out the interview HERE ! On this program, I play six works by Ileana Perez-Velasquez, Richard Barrett, Nina C. Young, Kaija Saariaho and Dai Fujikura, on violin, viola, and a detuned violin (borrowed for the day from the SPCO).

Liner notes for Melting the Darkness CD

“Melting the Darkness”

Notes by MC (Nov. 6, 2013)

This album ventures into regions of the art of violin-playing the significance of which is now becoming clear. Devoted entirely to microtonal compositions for violin and pieces for violin with electronics, this CD explores works of seven composers who have been challenged by these areas of discovery to create intriguingly fresh and surprising sound worlds.

Like opera singing and ballet dancing, the violin-playing tradition as situated within the Western classical heritage is a tremendously rich vein of history and achievement. It has involved a collective cultivation of craft and technique, an establishing of certain models of sound, and particular styles of virtuosity and performance that have been passed down through a couple centuries. I grew up, like many burgeoning violinists, steeped in this tradition, attending concerts by Nathan Milstein and Isaac Stern, studying with Dorothy DeLay and Robert Mann, listening to recordings by Kreisler, Elman, Oistrakh, Hubermann and more. These influences remain central to my musical identity on some level, as does the largely tonal, Baroque-to-Romantic repertoire that this violin-playing tradition addresses. I also cherish my many formative experiences playing chamber music, often with piano or other string players.

Since turning much attention in recent years to the music being written in my own time, I have found it fascinating to explore certain areas of experimentation that have taken my instrument beyond the familiar glories of its heritage. One of these is the use of microtonality- a system of intervals involving distances smaller than the half-step (the keys on a piano). I have been intrigued by both the physical aspects of working with such intervals, and the idiosyncratic ways in which composers use such intervals for their own expressive aims. Another interest has been noise- that is, non-pitched sounds, often percussive or abrasive, produced by unusual techniques on the instrument. A third area I’ve been eager to explore has been music involving electronics. Since electronic music’s beginnings, using spliced reel-to-reel tapes decades ago, the possibilities of the technology have exploded so that there are numerous ways in which to create or generate sounds and to interact, as a live performer, with them. This has led to a palette of sound possibilities and a degree of agility of response often not offered by traditional instruments.

Except for Iannis Xenakis, who died in 2001, the composers on this album are all artists with whom I’ve had wonderful collaborative friendships. We have worked together and they heard me perform these pieces live. The works by Burns, Sigman and Rowe were composed for me, and I was involved at certain stages of the pieces’ progress. While most of the works are essentially “dark”, having an overall atmosphere of anxiety, danger or sadness, each piece also has elements that affirm a sense of warmth, hope or clarity. The pieces on the CD are ordered in a way that I feel illuminates the interplay between dark and light in these pieces, and also the different ways in which the composers used the resources of microtonality, noise and electronics.

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), a Greek/French citizen, was not only a musician, but an engineer, architect, mathematician and author of major theoretical works on music. In his compositions, he incorporated ideas stemming from his scientific interests, pioneering electronic music, and applying stochastic and aleatoric processes, and set and game theory. While his works derive from highly cerebral concepts and treat sounds as objects put through experimental processes, the results are often surprisingly visceral and emotional. Tension and excitement build up as layers accumulate and clash, and the combination of control and disorder in the rhythm creates a wild sense of motion. Xenakis wrote “Mikka S” in 1976 following his first solo violin work, “Mikka” of 1971. Both pieces are based mainly on the glissando, a sliding pitch effect. Whereas “Mikka” consists of a single line, “Mikka S” ups the ante with two contrapuntal lines that move independently. At times, this requires extreme physical flexibility, as the violinist’s fingers must converge and cross directions, or stretch across strings. The two lines are in almost constant motion and frequently create a buzzing microtonal friction, but they coincide now and then on momentarily consonant intervals. Toward the end of the piece, the energy of the constant sliding erupts into boisterous bowed attacks and jagged, short glissandos.

Oscar Bianchi’s Semplice is a sparkling, virtuosic work in which fleet lightness subtly shades into something more anxious and spiky. Written in a relatively conventional violinistic style, with spiccato flourishes and flights to the upper registers, the piece’s short phrases take on a somewhat more aggressive cast in its middle section, in which microtonal intervals pervade the music and the scratchy noise of ponticello adds an edge of prickliness. Bianchi’s note:

Partly as reaction towards an overwhelming practice in our times of associating all sorts of notions of complexity with musical representation, I gave to this solo violin work the title of Semplice. This is the Italian word for “simple” or “natural”. Despite being based, as one hears rather quickly, on clearly non-simple musical material, this work aims towards an ideal of an organically simple way of playing. In a similar fashion, Gaudi found in nature an expression of simplicity made by highly articulated forms and complex phenomena. I wished to propose in Semplice a music in which gestures are constituted of subtle quarter-tonal inflections as well as minute, timbral definitions, compressed into quick, almost verbal (vocal) brilliance.

Georg Friedrich Haas has probingly explored the sonic, harmonic, and expressive possibilities of microtonality. His work uses minute intervals like eighth-, sixth-, and quarter-tones, and pitch relationships from the overtone series, causing intense beating of frequencies and “difference tones” that buzz along. In addition to generating a radical focus on sound itself, Haas’ insistence on microtonality has created new wells of expressive meaning in these relatively unfamiliar sonic distances. Resonating with the malaise and despair of much twentieth-century art, his music finds nuances of despondency and pain, but also surprising beauty, in the uncomfortable spaces between tones. Haas has revealed that, while composing de terrae fine (2001) on a sabbatical in Ireland, he was mired in a severe depression. The title, meaning “from the end of the world”, evokes not just an apocalyptic vision but a devastating sense of isolation. The music’s single line of winding microtonal motions seems to trace the twinges in a person’s lonely, anguished train of thought. Long tones swell in heaving sighs. At times, the overwhelming feeling of desperation gives way to a sickly nostalgia, with startlingly sweet double-stops and sliding arpeggios. About halfway through the work, the mood turns to anger, as pounding chords burst out. Moving upward by microtonal increments, the chords build in accelerating waves to a violent frenzy of raging despair- followed by a collapse into exhaustion, as a few wisps disappear into silence.

Christopher Burns composed Come Ricordi Come Sogni Come Echi after we had been working together on Luigi Nono’s La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura, an hour-long duo for violin and electronics. In Nono’s piece, the violin is a vulnerable, human protagonist amidst the ominous environment of recorded sounds. In Burns’ homage, this protagonist is taken out of the threatening context, and attention is focused on the intimate details of the violin sound, the grainy friction noise, and the warmth of the human voice, which, as in the Nono, joins in polyphony with the violin pitches. In the fourth and fifth movements, microtonal counterpoint creates a delicate tension. Burns writes:

I’ve been performing Luigi Nono’s La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura since 2002. Nono’s composition is one of my most cherished musical experiences as a listener, and my continuing work with the electronics part has been profoundly influential on my development as a musician. Composed in 2011, Come Ricordi Come Sogni Come Echi is a series of six studies exploring a few of the most intriguing elements from the violin part of Nono’s work, and seeking points of connection between La Lontananza and my own compositional idiom. The title (which translates from the Italian as “like memories like dreams like echoes”) is a performance instruction in Nono’s score, and reflects the ways in which Nono’s materials and ideas resonate through my homage. The piece is dedicated to Miranda Cuckson, whose thoughtful collaboration, detailed musicianship, and inventive approach to the performance of the Nono inspired the creation of these etudes.

Alex Sigman’s VURTRUVURT for violin and live electronics was commissioned for this recording. In this piece, the violin is a live denizen of an urban sound world, adding its startling noises to a world of machines. The electronics part is triggered and adjusted by an additional live performer. The piece was recorded in studio, after which the composer added some further sound processing and also created the spatialized imagining found on the 5.1 surround disk. Sigman writes:

V is for Vehicle and Volume, not Violin. U is for Union. R is for Resonance, Recording, Reflection...and T is for Trigger. VURT refers to the 1993 cyberpunk science fiction novel by Jeff Noon. Set in a dystopian Manchester, the novel chronicles the (mis)adventures of a gang of Stash Riders, who travel between Manchester and a parallel universe called Vurt. The boundary between the universes remains permeable, as Vurt creatures and events materialize on Earth. The sound sources employed in VURTRUVURT include elements evocative of the decaying urban and industrial environments described by Noon, as well as songs by Manchester bands of the 1980s-90s that were influential upon the his writing. These sources were also central to generating the violin material. In performance, the electronics are projected through a pair of small sound exciters: one attached to the violin, the other to a resonating glass surface. The violin thus becomes an electrified tension field, a physical point of actual/virtual intersection and cross-influence.

Ileana Perez-Velasquez’s work “un ser con unas alas enormes” is for violin and fixed media: the electronics were previously recorded onto a CD as one single track, with which the violinist performs in real time. The piece evokes a lush natural world with dangerous-sounding animal calls and insect noises in the electronics. Cuban motifs and a full-throated, heated lyricism characterize the violin part. Perez-Velasquez’s note:

“un ser con unas alas enormes”, which translates as “a being with enormous wings”, was inspired by the 17th Freeman Etude for violin by John Cage. Within the hectic gestures that are a major part of this etude are passages reminiscent of Cuban rhythms. An important idea for Cage is that human beings can be better themselves by overcoming their limitations. This piece translates that spirit; humans improve through the use of their imagination. The title is also related to the literary work by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, “un hombre muy viejo con unas alas muy grandes”. The tape part, as my departure of style, is fragmentary, and contains processed excerpts from the Freeman Etude. The piece also includes concepts of silence that are present in non-Western music. The use of silence as a conscious part of the piece yet again reflects back to Cage.

For Robert Rowe’s piece, Melting the Darkness, the violin part was written and recorded first; the composer then created the electronics as an accompaniment to the violin part, using processed snippets of the violin-playing, samples of percussion instruments such as the tabla, and other synthesized sounds. The violin propels the narrative of the piece, with a warm, largely conventional style of violin-playing. Rowe writes:

Melting the Darkness was written for Miranda Cuckson and commissioned by the New Spectrum Foundation. The piece is built around contrasting styles of music and performance, ranging from gritty, rhythmic phrases to more lyrical and slowly shifting sonorities. These contrasts are amplified and elaborated by an electronic commentary consisting of fragmented and processed material from the violin performance as well as a number of secondary sources. The title comes from The Tempest (as it should when a piece is composed for Miranda): “…as the morning steals upon the night, Melting the darkness…”

thoughts on music at the new year

I woke up this morning with these thoughts in my head so I wrote them down:

Here’s to

– music as a lifelong endeavor and part of personal growth

– the passion of music

– the flow of music in time

– the mathematics and science of music

– music’s ability to express anything

– the physicality of playing music

– the physicality of the dance in music

– the disembodied selflessness of feeling in the moment that you are only in service of the music, of wanting that phrase or sound to express what it wants to express, of making the music “happy”

– the communality and liveliness of a concert and putting on a show

– the ephemerality and unpredictability of the live moment in music

– the many hours of preparation and work before a performance

– the sculpting of sound and music in the recording studio

– the complexity of recording and making recordings, the spontaneous and the mulled over, the purity of focus and the act of documenting people, the making of a thing like a book or film or painting

– beautiful tones

– breathing and furniture creaking

– listening to lots of music

– sometimes not listening to music

– talking and writing about music

– not talking and writing about music

– thinking about anything

– the ambience of a casual concert

– the ambience of a formal concert

– meeting with and talking with people at and after concerts

– being alone with your thoughts after playing or hearing a concert

– entertaining while enjoying and responding to an audience’s responses, facial expressions, applause

– becoming unaware of anything at all but your innermost, nonverbal feelings while playing, the deepest emotions tapped into by the music

– discovering unfamiliar music

– playing pieces you know many times

– wanting to give people a terrific and fun experience for those couple of hours

– an easy phrase or flourish

– sharing music as a communally cathartic, non-escapist confronting of serious reality

– stretching your being by pushing your art forward while feeling the emotional ties to the past

– traveling a lot and being thankful for the ability to travel, which makes it possible to see different places, and mainly, to be with people

– enjoying the familiarity of home and treading the well-worn sidewalks of one of the world’s great cities

– recognizing life’s many facets and paradoxes

– when dealing with the murk of misunderstanding, working with others to reach the happiness of clarity, strength and integrity

– love of musicians

[This was originally a Facebook post in 2014 but it somehow disappeared. Thanks to John Darnielle, great musician and writer, who reposted it back then on his Tumblr.]

Ralph Shapey, Beethoven, and Dotted Rhythms

Ralph Shapey, Beethoven, and Dotted Rhythms: a Violinist’s Point of View

by Miranda Cuckson

For the violinist, Ralph Shapey’s compositional output offers an abundance of challenges and strikingly expressive music. Shapey wrote for the violin throughout his life, producing a large catalogue of works for the instrument. These include eight solo pieces, most of them multi-movement; seven pieces for violin and piano; six works for violin with orchestra or ensemble, including the Invocation-Concerto (1959) and a concerto entitled The Legends (1999); and duos with viola, cello, and voice. He also wrote numerous chamber works involving the violin, including ten string quartets, several trios, and many ensemble pieces.

When I planned my first album of Shapey’s violin music,1 I was just beginning to explore his work. I chose to record five pieces spanning his compositional career: Etchings for solo violin (1945), Five for violin and piano (1960), Partita for solo violin (1965), Mann Soli for solo violin (1985), and Millenium Designs for violin and piano (2000). In working on these pieces, I found that getting to know his music from a violinist’s standpoint is extremely interesting. In addition to the expressive satisfaction the pieces afford, they reveal a great deal about his compositional preoccupations and evolution, while also evincing his substantial background as a violinist.

During the early part of his musical life, Shapey was very active as a performing violinist. He began to play the instrument at age seven, and soon displayed much natural ability. In his teens, he studied with Emmanuel Zetlin, a former assistant to the pedagogue Carl Flesch. In the summer of 1945, he took lessons with Louis Persinger, the teacher of Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern. Shapey learned much of the standard solo repertoire, including such pieces as the Beethoven and Sibelius concertos, the Bach Partitas and Sonatas, and the Wieniawski etudes. He went on to freelance as a performer, working with artists including Adolf Busch and the Juilliard Quartet. Violinist Robert Mann was a close friend of Shapey, and describes him as “a decent performer with a fluent command of the instrument.”[i] In the early 1950s, Shapey stopped playing, deciding that his composing and conducting projects left him too little time to practice. He taught violin for a time, in addition to composition and theory, at the Third Street Settlement School in New York.

In writing his own violin music, Shapey remained devoted to the instrument’s traditional qualities, while audaciously pushing the limits of conventional violin-playing technique. Unlike composers such as George Crumb, Luigi Nono, Krysztof Penderecki, and Luciano Berio, who investigated “extended” techniques involving non-pitched noise, percussive strokes, and microtonality, Shapey innovated by expanding upon the fundamental attributes of traditional violin playing – in particular, the capacity for lyrical melody, and for polyphonic, chordal textures. His pieces demand the familiar violinistic essentials – resonant tone, pure intonation, clear articulation – but feature linear shapes and chords requiring extraordinarily large left-hand stretches, unorthodox fingerings, quick leaps around the fingerboard, and adept string changes in both staccato and legato contexts. Shapey’s approach to writing for the violin recalls Leonard Meyer’s well-known description of him as a “radical traditionalist.” Shapey emulated the structures and motivic ideas of Beethoven, Brahms, and Haydn, while breaking away from tradition in his gestural and harmonic language. Similarly, he drew upon the techniques of traditional violin-playing, opening up new expressive possibilities of the player to extremes.

Shapey’s violin works are especially fascinating because of this intersection of his musical and communicative aims with his physical approach to the instrument. Though the technical puzzles he poses for the player are absorbing in themselves, those challenges are intrinsic to his expressive intentions. The huge intervals, leaps, and chords all contribute to what is probably the most pervasive characteristic of his music: its quality of expansiveness. Shapey wrote music with big dimensions – hefty, contrasting sections, dramatically wide-ranging melodies, and ruggedly distinct contours. At the same time, he exploited the physical characteristics of violin technique, with wide left-hand distances to be covered, and sometimes complex string crossings, in order to convey an expansive sense of space and time.

In all of the five works that I recorded, I observed a particular musical kernel that intriguingly relates to many of Shapey’s preoccupations, both expressive and technical: the dotted rhythm. This simple motive is featured prominently in all of these pieces, and indeed in much of Shapey’s oeuvre, with such frequency that it seems to have been something of an obsession for him. This makes sense when one notes that Shapey idolized Beethoven, and spoke often of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, Opus 133. The Grosse Fuge was performed by the Juilliard String Quartet at Shapey’s memorial service.[ii]

The Grosse Fuge, of course, presents remarkable ongoing strings of insistent, dotted rhythms. As Robert Carl relates, Shapey liked to tell people that he had spent a year studying Beethoven’s music, and that of Haydn, Mozart, and Brahms, in order to determine for himself the source of the strength of their compositions. He decided that this lies in the distinctiveness of their musical material, the almost tangible quality of their motives. Inspired by their example, Shapey described such concrete, compact musical ideas as “graven images,”[iii] or as musical “objects in space.”[iv]

In the Grosse Fuge, Beethoven used the dotted figure as a self-contained musical “object,” a building block that is the defining rhythmic element of the music, one with which he constructed whole passages and sections of the piece. The dotted rhythm possesses inherent musical traits that make it a vivid and intriguing compositional element with which to work. Its strongly articulated main beat makes it a firmly grounded pulse (whether or not the next beat is articulated or not), and its rhythmic components (long note plus short note) form an immediately recognizable shape. In contrast to the more horizontal directionality and constant motion of equal-valued notes, the dotted rhythm has a vertically weighted feel, and, in moderate to fast tempos, a natural jauntiness that denotes energy and liveliness. The rhythmic position of its shorter note can, however, affect the character of the motive in a variety of ways, depending on how it is played. It can rebound from the impetus of the main note, and pull briskly towards the next beat, propelling the motive forward, or creating momentum in a passage of continuous dotted rhythms. If purposefully delayed, it gives the figure a resistant and stubborn, or majestic and massive, character. If combined with intervallic leaps, the dotted rhythm possesses an extra measure of drama, conveying the sense of distances being crossed in a spurt of energy. Such leaps are a striking characteristic of the Grosse Fuge (see Fig. 1, mm. 30-31, or mm. 38-42), again suggesting that Shapey took inspiration from Beethoven’s work and seized upon its elements for his own creative purposes

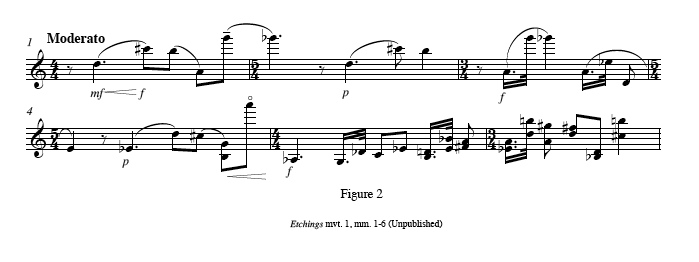

The dotted rhythm is prominent in the three faster movements of Shapey’s Etchings, an early solo work dedicated to Louis Persinger. The five short movements are variations of contrasting character. The piece is neoclassical in style, with frequently changing meters, and a spare monophonic texture that is sometimes enriched by double-stops. In this context, the dotted rhythm takes on an elegant, Classical, character. The “object” is tidily contained within the constraints of the meter’s pulse and its subdivisions. The rhythm appears frequently in the lively first movement, Moderato. It is first introduced in measure 3, incorporating a descending half-step motive introduced in mm. 1-2 (Fig. 2).

Shapey’s predilection for large leaps is already evident in the first bar’s wide-ranging intervals, the major seventh, D-C#, the major ninth, B-A, and the minor fourteenth, A-G. The expansive gestures of m.1 are restated in m. 3 in diminution, with the quick dotted rhythms enhancing the sense of acrobatic nimbleness.

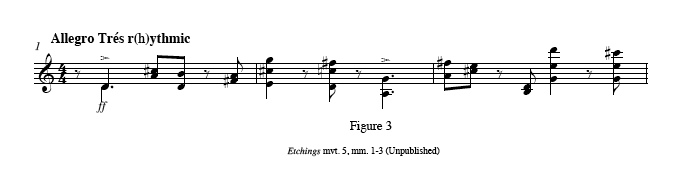

The third movement, titled Moderato vigoroso marciata, is primarily in 4/4. It is composed entirely of homophonic double-stops. Its many dotted rhythms are self-evidently march-like. The fifth movement, Allegro très rhythmic, is faster, and features syncopations and more irregular rhythmic patterns (Fig. 3).

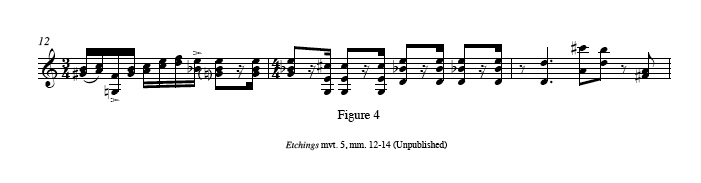

The rhythmic agitation of this movement causes the dotted rhythms to be more insistent in their forward motion. Their tendency to press onward to the next beat culminates in the triple stops in mm. 12-13 (Fig. 4). The last sixteenth note of m. 13 jumps into silence on the first downbeat of m. 14, toying with the expectations of the listener, as a syncopated beat arrives in place of the dotted rhythms of the previous measure.

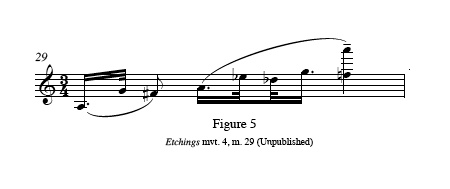

Overall, Etchings shows signs of Shapey’s interests in wide-ranging lines and chordal playing. However, aside from some large leaps, it does not pose the degree of technical challenge that he later explored. A hint of more complex technical problems occurs in m. 29 of the fourth movement, Andante cantabile, where a reversed dotted rhythm moves, legato, from a G to an F-A double-stopped tenth, a somewhat awkward move for the left hand to negotiate (Fig. 5). Perhaps Shapey reversed the rhythm to facilitate the movement of the hand. In any case, given the languid, lyrical mood of the passage, it seems musically appropriate to stretch the end of the beat, and ease into the double-stop. The high A emerges delicately and surprisingly as the G moves to the F underneath.

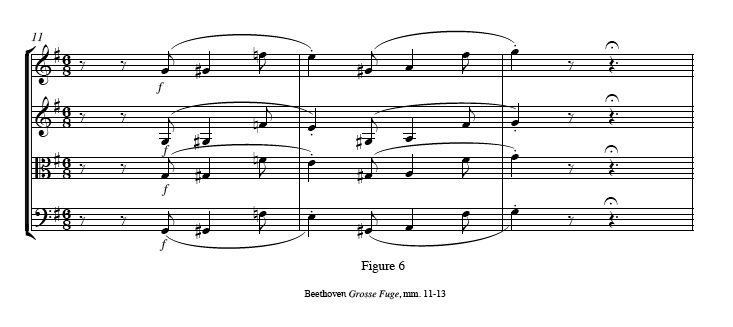

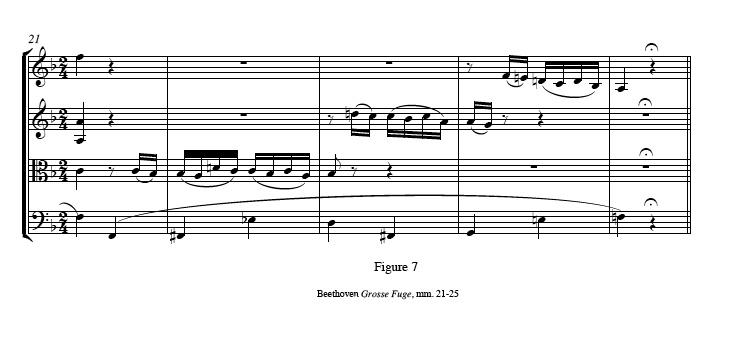

In Five, Shapey explored a rhythmic sense in which precise, firmly defined rhythmic ideas exist within a meter-less context, engendering a tension between precision and freedom. In this five-movement piece, Shapey worked with the dotted rhythm, extracting its essential gesture, and transforming it into various guises. This technique is somewhat reminiscent of Beethoven’s handling of the dotted-rhythm motive in the Grosse Fuge. Beethoven turns the motive into related forms. He employs ternary groupings of quarter notes and eighth notes (Fig. 6), and sixteenth note patterns in which the last of four sixteenths is the same pitch as the first of the subsequent group, suggesting a dotted rhythm (Fig. 7).

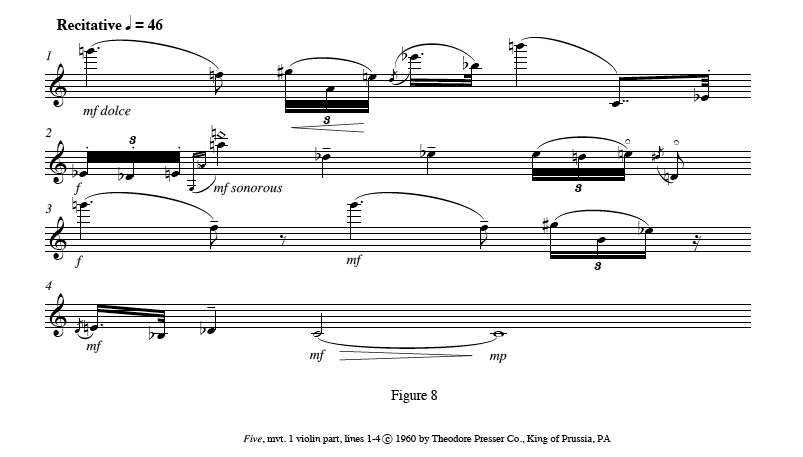

Rather than focus on the whole motive, Shapey concentrated on the upbeat gesture inherent in the dotted rhythm. In the opening Recitative movement of Five, the violin begins with a straightforward, broad dotted rhythm: a dotted quarter note plus an eighth note, in a tempo of quarter note=46. Shapey then presents several brief musical ideas in succession: a quick triplet, a single grace note, then an actual dotted rhythm. These all function as rapid upbeat gestures, each giving the effect of a dotted rhythm’s short note, leading into another event (Fig. 8).

Wide intervals abound: the opening G drops a major ninth to F, and the quick Eb–Bb dotted rhythm leads to a high B, requiring a fast left-hand shift. This pitch is a third higher than the opening G, producing a dramatic line of high peaks. A descent to the violin’s lower register brings about another series of “upbeat” gestures: a double-dotted rhythm, a triplet, and a two-note grace-note figure. These gestures lead to an A harmonic, the highest pitch so far.

Shapey employs these triplet and grace-note upbeat figures throughout the movement. Because of the absence of both meter and a regular pulse, the dotted rhythm gesture generates points of pronounced emphasis, and motion toward those points. The rhythm serves to create “objects” which exist in a free expanse of time. When strung together in a quick series, the gestures suggest both a repeated thrust toward a goal, and a certain awkwardness or struggle, comparable to climbing over a pile of rocks in order to reach a higher level.

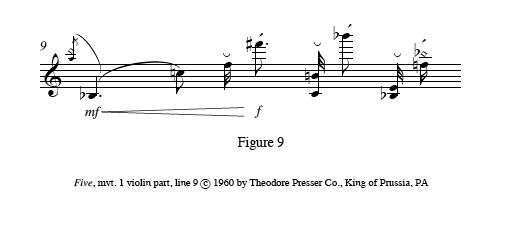

In evoking the dotted rhythm idea, Shapey often clarified his intention by writing symbols indicating “upbeat” and “downbeat,” a notation that he used in line 9 of Five (Fig. 9).

The sense of spaciousness created by this passage is especially dramatic, as the violin roams in an extended solo, untethered to the piano part. Shapey’s “downbeats” create an unsettling, jagged character. Shapey also uses the dotted rhythm as a conventional, emphatic closing gesture, as in line 4 (which is repeated at the end of the movement ) (Fig. 8).

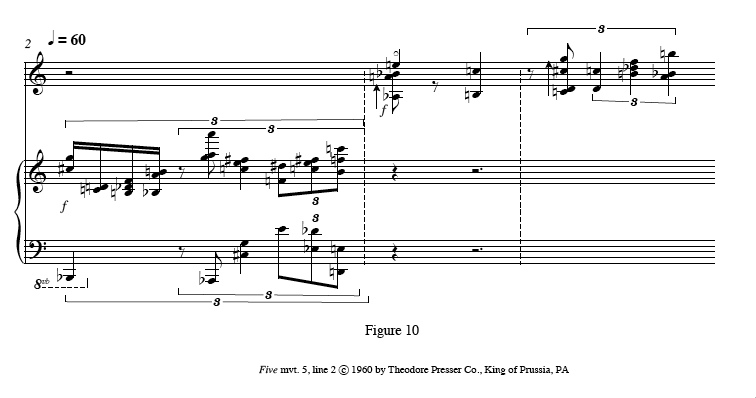

Dotted rhythms do not play much of a role in the rest of Five. However, the last movement contains one other transformation of this rhythm that can be seen in Shapey’s other works: chords. Chordal playing on stringed instruments usually necessitates that the notes be somewhat arpeggiated, because the bow must traverse the curve of the bridge as it contacts the strings. This causes a grace-note-like effect that can also be interpreted as a kind of dotted rhythm, depending on how the “upbeat” notes are articulated or lengthened. Shapey maximized this effect by writing chords involving not only all four strings, but also large intervals, and left-hand positions requiring unusual extensions and knotty fingerings. Consequently, there is an added measure of time and effort involved in crossing from one side of a chord to the other. He also often included dissonant, clashing intervals within the chord, creating timbral tension. For example, the first violin chord of the fifth movement is Ab-A-Bb-E. This requires a moderate stretch from Ab to A, plus a movement of the first finger from the Ab on the G string over to the Bb on the A string, necessitating an arpeggiation. The minor second, A-Bb, and the tritone, Bb-E, inject jolts of dissonance, which lead into the sound of the bright, sustained open E string (Fig. 10)

In the next “bar” (Shapey used dotted bar lines here), B-Db-F is an especially awkward chord, which I choose to play by shifting from a double-stop in second position (B-Db) to one in first position (Db-F). This splitting of the chord into two components creates an aural result similar to that produced by the broken chords around it, and is in keeping with the heavy, laborious character of the passage.

The various dotted rhythm gestures seen in Five are plentiful in Shapey’s Partita, written five years later. Like Five, this three-movement solo work features a great deal of chordal writing, involving complex, tangled fingerings and wide intervals. The intervals are often dissonant, so it is important to use sweeping arm movements to draw rich sound from the strings, so that the pitches resonate and can be heard clearly. The frequent splitting or arpeggiating of the piece’s numerous chords contributes to the craggy robustness of the music.

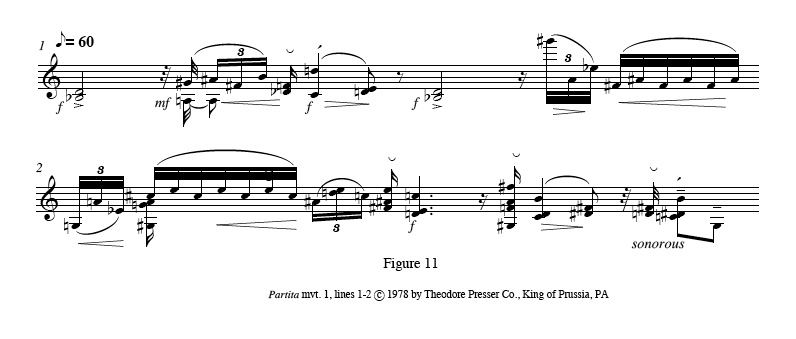

In addition to chords, Shapey makes much use in the Partita of quick upbeat triplets, and also employs his upbeat and downbeat symbols. As in Five, these symbols serve a meaningful purpose, for the rhythmic emphasis can be ambiguous unless elucidated by the player. There are no bar lines in the first two movements, so the rhythmic values and patterns are irregular and the main emphases come at unpredictable moments.

In the first movement, a theme and five variations, melodic and rhythmic units recur in modified forms, or are rearranged in different orders. In the opening sections, the ideas are grouped into fragments. The music progresses in compact, declamatory bursts. Long, sonorous tones are often preceded by sixteenth notes, on which Shapey placed upbeat symbols. The upbeats are usually double-stopped or chordal, requiring firm bow articulation (Fig. 11).

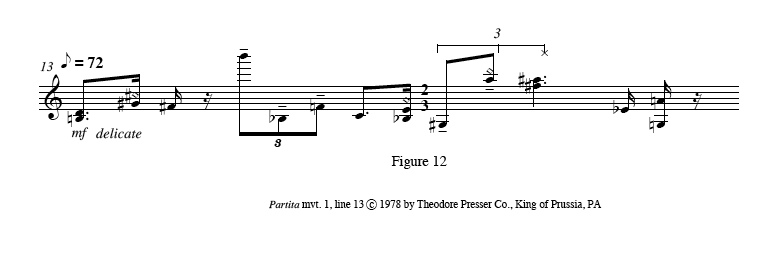

The beginning of the scherzando third variation presents a more continuous line, which jumps delicately across wide intervals. In this variation, the dotted rhythm is one of several small rhythmic cells that are strung together horizontally, including triplets, parts of triplets, and single eighth notes. As the various motives alternate, there is little sense of any beat or pulse, and the dotted rhythm becomes less distinct as a recognizable “object,” its components now forming part of a disjointed rhythmic line (Fig. 12).

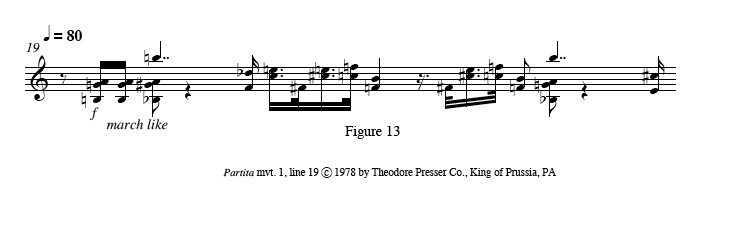

The fourth variation is labeled “march-like.” Its dotted rhythms move twice as fast as those in the preceding sections (FigEx. 13). Mostly double-stopped, these rhythms require clean attacks to project their crispness. The variation also includes weighty four-note chords, involving awkward left-hand fingerings. The effort entailed in breaking the chords clearly is again an important factor in conveying the expressiveness of the music.

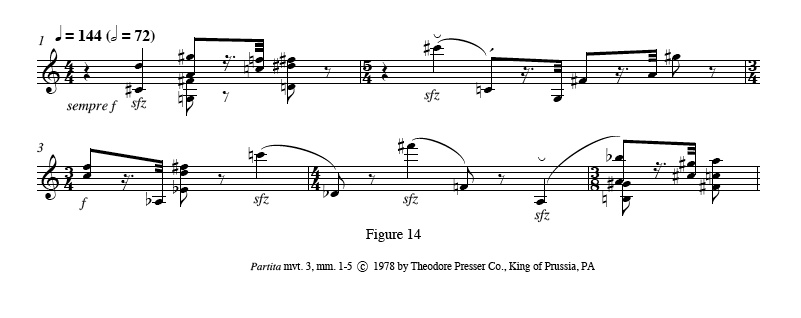

The third movement of the Partita consists of a Grosse Fuge-like series of dotted rhythms. In this case, the rhythms are actually double-dotted, a characteristic which imparts an especially jaunty springiness to the music. The dotted-rhythm “objects” are grouped into short phrases that usually open with a quarter note or eighth note sforzando upbeat. These sforzando attacks (marked with an upbeat symbol at their first few appearances) are basically an exaggeration and elongation of the upbeat idea. Their weighty gravitational pull counterbalances the airborne lightness and clipped quality of the thirty-second note in the double-dotted rhythms (Fig. 14).

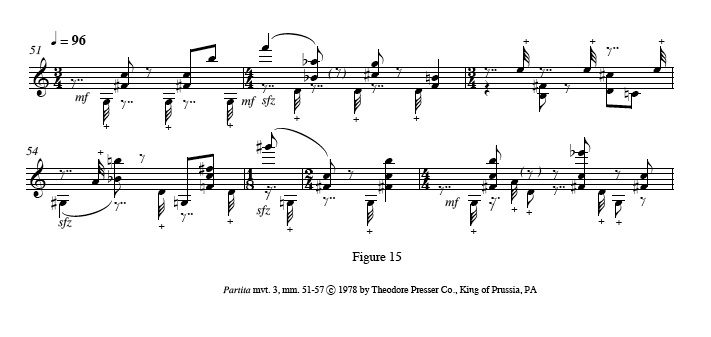

In the movement’s middle section, beginning in m. 51, Shapey turned the double-dotted rhythm into a witty and technically tricky figure. He transformed the upbeat thirty-second note into a left-hand pizzicato, which leads in most instances to a bowed double-stop. The pizzicati are played on open strings, facilitating their execution and requiring clean and quick moves from pizzicato to arco (Fig. 15).

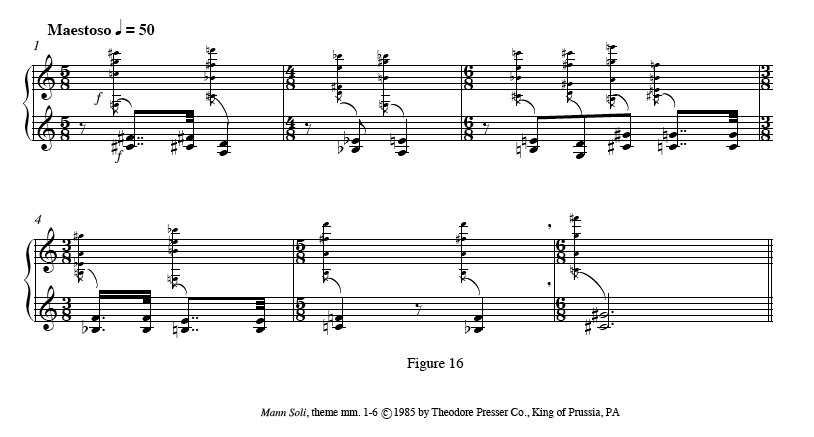

Mann Soli is composed of a theme and five variations, the theme returning at the end of the piece. The dotted rhythm is a central element of the material. The maestoso theme is written across two staves, the lower staff with the primary rhythm and pitches, while four-stringed grace-note chords are placed on the upper staff. (Fig. 16). The lower staff’s “melody” is in double-stopped fourths or fifths, and moves at a steady pace. Grouped into a few short phrases, it features weighty, double-dotted rhythms in the first measure and mm. 3-4. This powerful, declamatory line serves as a rhythmic foundation for the grace-note chords attached to it. Massive and very intense, with their wide intervallic range, strikingly dissonant intervals, and bright topmost notes on the E string, these chords must be split into two double-stops, essentially forming two-note grace-note figures. They repeatedly deliver huge upbeat motions that land forcefully on the subsequent beats of the theme. When combined with the main line’s own dotted rhythms, they produce a series of three upbeat articulations, fired off in a row with jarring intensity.

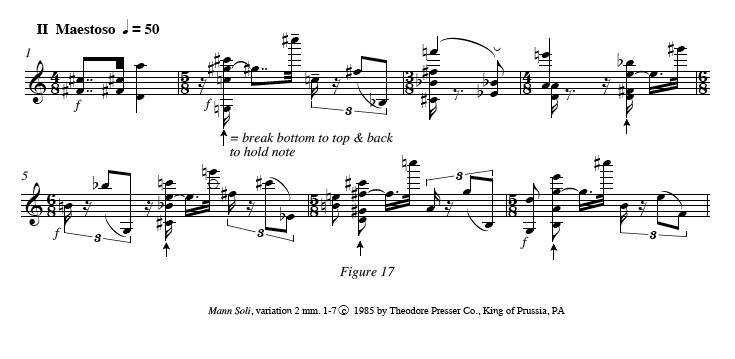

The first variation incorporates the dotted rhythm simply, with a single dotted figure opening each phrase. In the second variation, Shapey again employs the double-dotted rhythm, as he turns the theme into a primarily monophonic line that jumps around across an enormous pitch range (Fig. 17). The violin writing includes many vaulting left-hand leaps. Elaborate four-note chords punctuate many of the variation’s longer sustained notes. These chords directly recall the grace-note chords in the main theme, both in their intervallic make-up, and in the rhythmic effect of their arpeggiation. Shapey ties the second-highest pitch in each chord into the following held note, and writes, “break bottom to top & back to hold note,” along with a symbol that combines two arrows, one pointing upward, the other curving back downward. This kind of bi-directional arpeggiation is an established technique among string players, and is sometimes used in polyphonic works, such as the solo sonatas of Bach, in order to bring out specific inner lines. Shapey’s employment of the device serves that purpose, while replicating the swooping motion of the opening theme’s grace-note chords, which break upward in two double-stops, then veer back downward to arrive on the main notes.

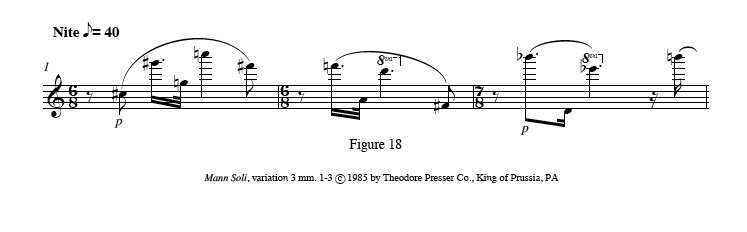

In variation 3, dotted rhythms appear as part of a legato melodic line that moves by large intervals between the violin’s middle and high registers (Fig. 18). Quiet and spare, the variation conveys a remarkable sense of vast expanses of space and time. While the melody is essentially slow-moving, the dotted rhythms gently nudge it forward, with quick motions toward the subsequent beats. The large leaps in the dotted rhythm figures suggest a tightrope walker, making exquisitely graceful leaps above an open expanse.

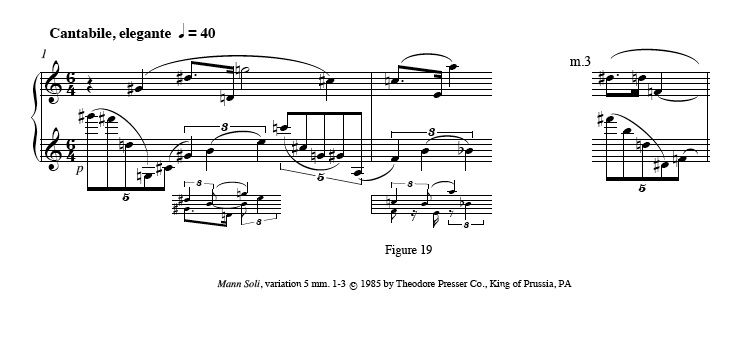

The fourth variation is based entirely on dotted rhythms, bunched in brief phrases that halt on double- or triple-stopped chords, played on strong beats. In the fifth variation, the dotted rhythm is subsumed into a contrapuntal, polyrhythmic texture in which two cantabile melodies, written on separate staves, are played simultaneously. The two lines are closely entwined, crossing each other registrally, and interlacing disparate rhythms. The dotted rhythm is combined with large leaps, forming graceful, Romantic gestures, and leading the long, meandering phrases toward points of expressive focus (Fig. 19).

Since it is technically impossible to play both melodies at once, one must foster this illusion by seamlessly alternating between the voices and employing unusual fingerings. Shapey provides little clue as to how to execute the passage. There are various possible solutions, depending on which tones one chooses to sustain or drop. In m. 1, I play the two lines simultaneously by momentarily dropping the D# on the A string to play the B with the first finger. The B is then double-stopped with the open D string, and with the G on the E string. In this way, the dotted-rhythm leap is traversed, while both lines are continuously sustained. In m. 2, I choose to drop the lower line at the leap. Leaving the B-E fifth that occurs on the last sixteenth note of beat 1, I shift to fourth position for the A, playing it alone before bringing in the B flat on the D string on the second triplet of that beat. This allows for a smooth technical transition, and also creates a moment of open space in which the A sings through.

In this variation, the dotted rhythm is sometimes a passing element in the fluid texture of the music, rather than a focal point. In m. 3, it is placed against an eighth note quintuplet. The two lines are briefly entangled, then unspool, as the dotted rhythm occurs simultaneously with the quintuplet. At the point where the two rhythms intersect, the lines share a common pitch, D natural, which ties them together momentarily, and obfuscates the rhythmic distinction of the dotted figure (Fig. 19).

I play the upper-line D with the first finger, combining it as a unison with the lower-line D, played with the fourth finger on the D string. The fourth finger is then double-stopped with the F, played with the third finger on the G string. In order to sustain both lines, I shift to second position, moving the F to the first finger on the D string. The D# and F in the quintuplet are played on the G string.

Whereas Shapey’s music of the 1960s-80s is freely gestural and fragmented, his late works show a return to long lines and a strong metrical pulse, with simple rhythmic ideas interlocking in a dense web. Millenium Designs, for violin and piano, presents swathes of neatly meshed counterpoint, in which rhythm and texture are more important than melody. Formed of sections that recur in different movements, the piece is a large-scale patchwork of shifting characters. The dotted rhythm is very prevalent in this piece. It bears traits of both the weighty upbeat gestures of his middle-period music, and the Classical elegance of his early pieces.

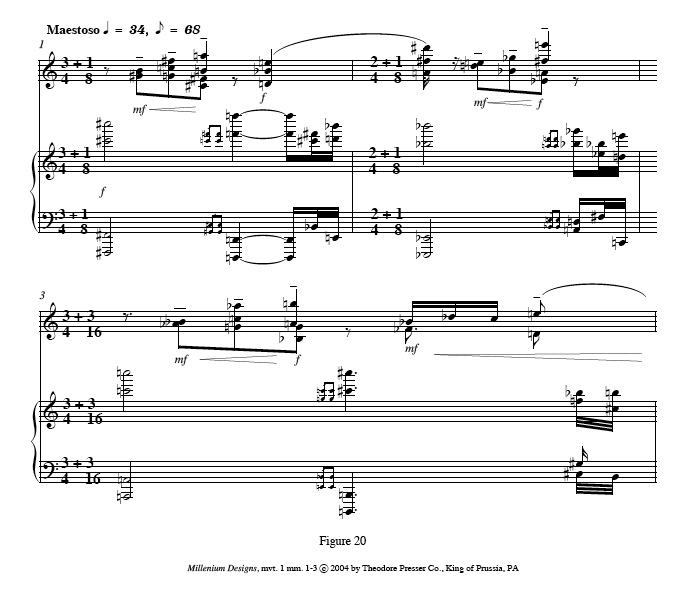

The opening is a mighty refrain that returns both at the end of the movement and the end of the work. The instruments establish a slow eighth-note pulse as they alternately play heavy chords. The dotted rhythm is present by virtue of the violin’s splitting of the chords, which pushes the motion onward, while also evoking a sense of labor and struggle. In the violin’s repeated gesture of three eighth notes, Shapey increases the effect of the crescendo by making the last of the three a four-note chord, typically involving dissonant intervals and awkward fingerings. The piano’s chords are insistent, with upbeat gestures comprised of pairs of either grace notes or thirty-second notes (Fig. 20).

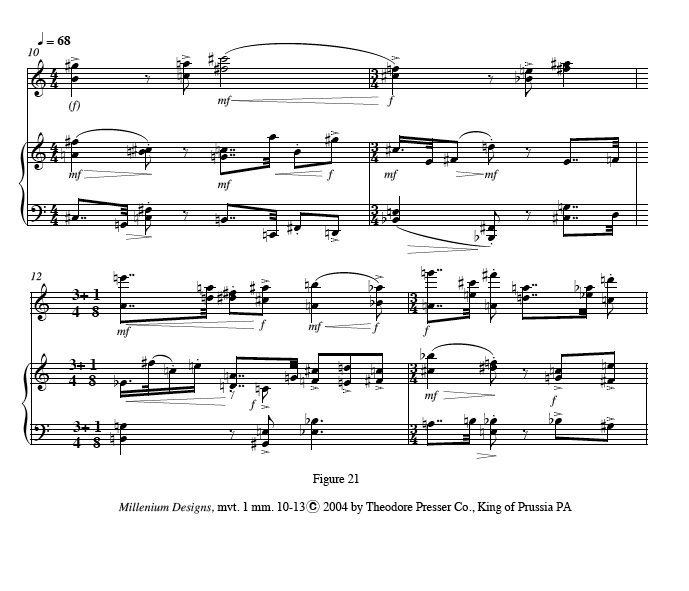

In much of the rest of the piece, the dotted rhythm is tightly locked within an eighth-note-based framework. The squareness of the rhythmic cells and neatness of the “objects” harks back to the neoclassical character of Etchings. In Millenium Designs, the dotted rhythm suggests certain emotional traits. In sections of moderate tempo, such as m. 10 in the first movement (Fig. 21), it creates a gentle tension, as the listener waits momentarily for the arrival of the next note. Shapey sometimes enhances this effect by double-dotting.

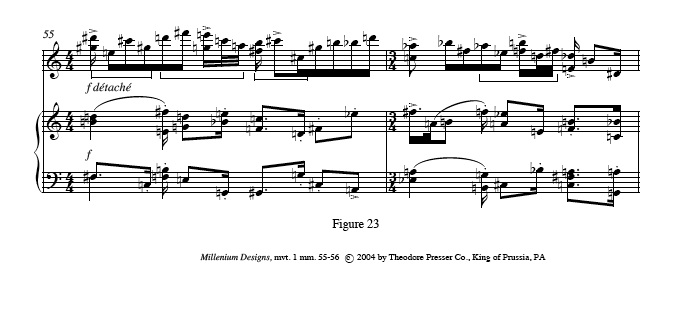

In faster sections (Fig. 22), the dotted rhythm has a jaunty character, conveying a more vertical stress, even as the music proceeds in a linear fashion. This jauntiness contrasts with the firmness and swagger of the section beginning at m. 55, where the violin plays groups of notes of equal value (Fig. 23).

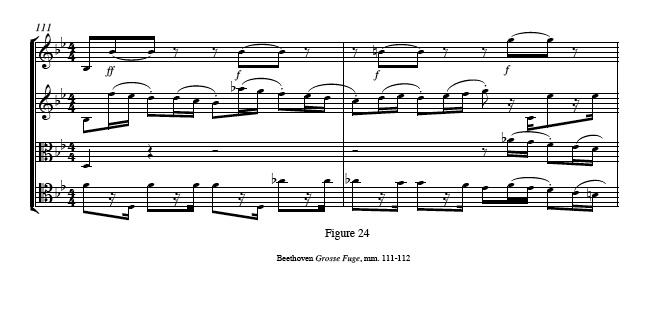

Shapey’s manner of interlocking the dotted rhythm with other rhythmic units can be likened to Beethoven’s procedure in passages of the Grosse Fuge. At m. 111, the dotted rhythm is played by the cello, landing on the beginning of each beat of the 4/4 bar (Fig. 24). It is combined with the second violin’s repeated anapestic figure of two sixteenth notes leading to an eighth note, and with the first violin’s cross accents on the second half of beats 1 and 3. This layering of rhythms creates a texture in which one hears several discrete lines simultaneously, with emphases occurring one after the other in quick succession.

Beethoven was clearly the main exemplar of Shapey’s musical ideals. Even more than Haydn, Mozart, or Bach, Beethoven invested the individual motive with charged expressive significance, giving his music the etched impact of a “graven image.” The powerful character of Shapey’s music, whether rugged and bold, or ethereal and lyrical, is especially close in spirit to that of Beethoven. Furthermore, Shapey’s idea of virtuosity seems particularly akin to Beethoven’s. Although both composers sometimes brought agile brilliance to the fore, they often embraced a sense of physical exertion, making it an expression of strength in their music. Beethoven’s music sometimes appears blatantly to disregard the norms of idiomatic instrumental writing, aiming instead for a purely musical objective. His works can be very unidiomatic for stringed instruments, using patterns often more suited to the piano. With his knowledge of the violin, Shapey worked to push the performer to the extremes of established technique, designing technical challenges to convey the toughness, strenuousness, and spaciously dramatic qualities of his music. In this way, his pieces achieve the near-tangibility of their musical ideas through the physicality of their execution, and they expand the range of expression that virtuosity can supply.

1 Music by Ralph Shapey, Centaur CRC 2900. Miranda Cuckson, violin, Blair McMillen, piano.

[i] Robert Mann, interview by author, New York, 4 September 2007.

[ii] Anthony Tommasini, “Music; Rugged Music Once Packaged in Plain Brown,” The New York Times, 10 November 2002.

[iii] Robert Carl, CD liner notes, Ralph Shapey: Radical Traditionalism, New World Records 80681-2.

[iv] Cole Gagne and Tracy Caras, Soundpieces: interviews with American composers (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1982),

My meeting with Henri Dutilleux

Henri Dutilleux was one of the great artists of the last century and a wonderful man, and I treasure my memories of meeting him and playing for him in Paris one summer. Following the very saddening news of his death, Sequenza21 asked me to write about my visit with him. My little essay is now posted here on the Sequenza 21 site, also here on Tumblr (with larger photos). (A note: M. Dutilleux wrote the date wrong in his dedication on my score. It was 2001.)