Ralph Shapey, Beethoven, and Dotted Rhythms: a Violinist’s Point of View

by Miranda Cuckson

For the violinist, Ralph Shapey’s compositional output offers an abundance of challenges and strikingly expressive music. Shapey wrote for the violin throughout his life, producing a large catalogue of works for the instrument. These include eight solo pieces, most of them multi-movement; seven pieces for violin and piano; six works for violin with orchestra or ensemble, including the Invocation-Concerto (1959) and a concerto entitled The Legends (1999); and duos with viola, cello, and voice. He also wrote numerous chamber works involving the violin, including ten string quartets, several trios, and many ensemble pieces.

When I planned my first album of Shapey’s violin music,1 I was just beginning to explore his work. I chose to record five pieces spanning his compositional career: Etchings for solo violin (1945), Five for violin and piano (1960), Partita for solo violin (1965), Mann Soli for solo violin (1985), and Millenium Designs for violin and piano (2000). In working on these pieces, I found that getting to know his music from a violinist’s standpoint is extremely interesting. In addition to the expressive satisfaction the pieces afford, they reveal a great deal about his compositional preoccupations and evolution, while also evincing his substantial background as a violinist.

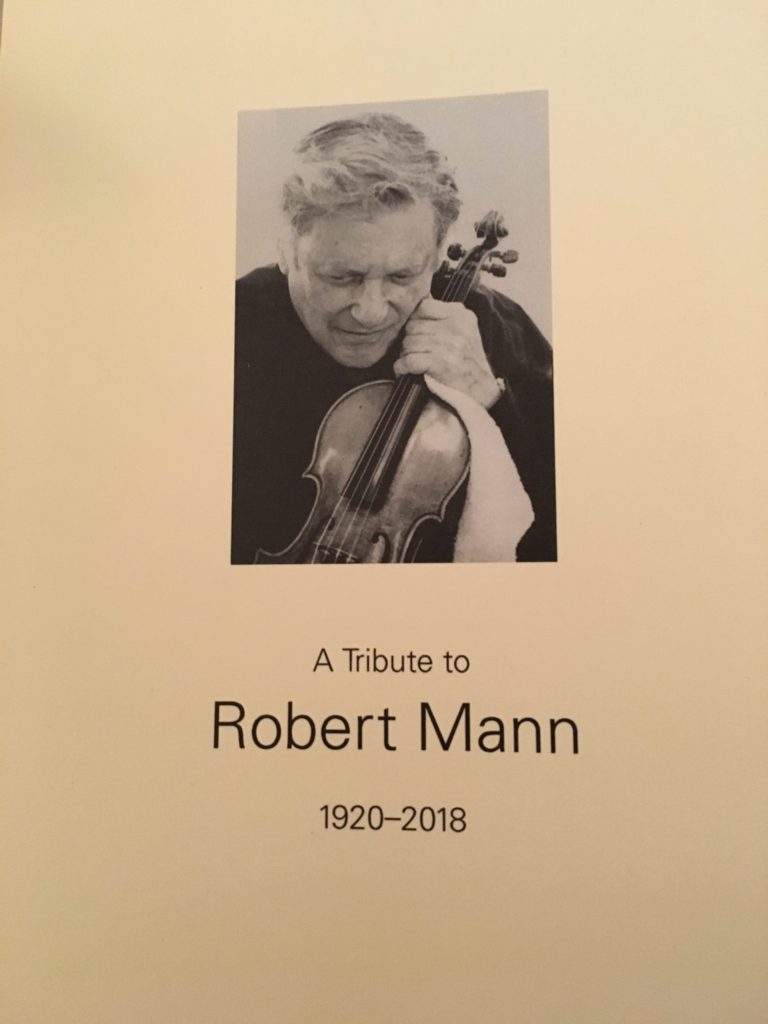

During the early part of his musical life, Shapey was very active as a performing violinist. He began to play the instrument at age seven, and soon displayed much natural ability. In his teens, he studied with Emmanuel Zetlin, a former assistant to the pedagogue Carl Flesch. In the summer of 1945, he took lessons with Louis Persinger, the teacher of Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern. Shapey learned much of the standard solo repertoire, including such pieces as the Beethoven and Sibelius concertos, the Bach Partitas and Sonatas, and the Wieniawski etudes. He went on to freelance as a performer, working with artists including Adolf Busch and the Juilliard Quartet. Violinist Robert Mann was a close friend of Shapey, and describes him as “a decent performer with a fluent command of the instrument.”[i] In the early 1950s, Shapey stopped playing, deciding that his composing and conducting projects left him too little time to practice. He taught violin for a time, in addition to composition and theory, at the Third Street Settlement School in New York.

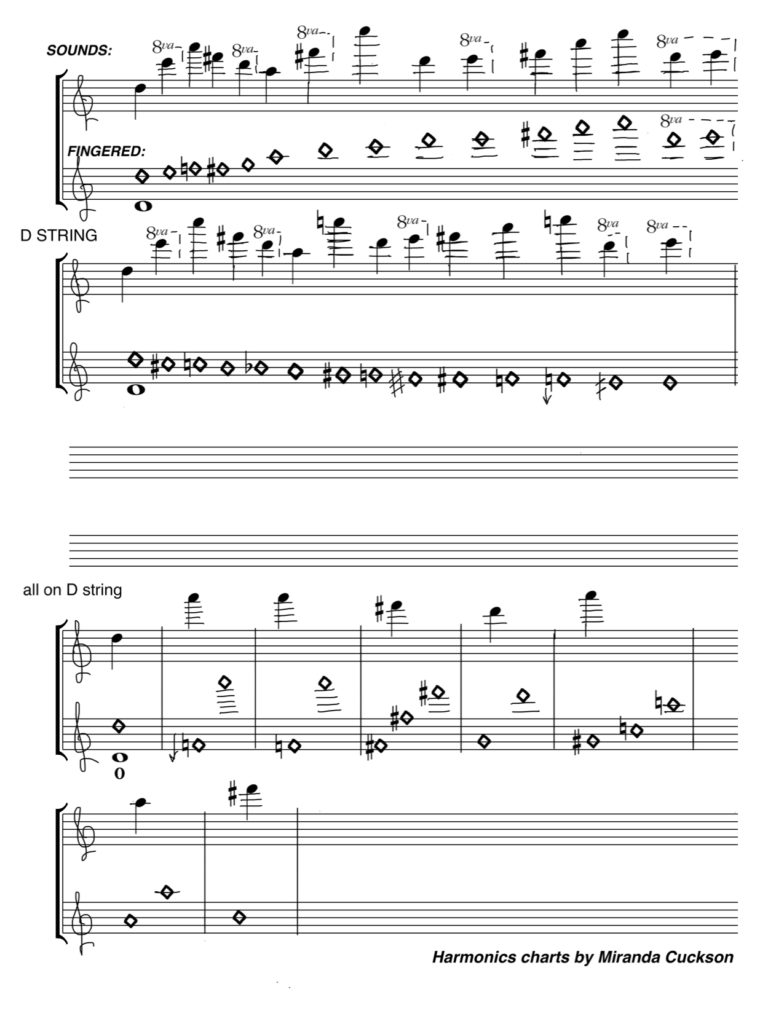

In writing his own violin music, Shapey remained devoted to the instrument’s traditional qualities, while audaciously pushing the limits of conventional violin-playing technique. Unlike composers such as George Crumb, Luigi Nono, Krysztof Penderecki, and Luciano Berio, who investigated “extended” techniques involving non-pitched noise, percussive strokes, and microtonality, Shapey innovated by expanding upon the fundamental attributes of traditional violin playing – in particular, the capacity for lyrical melody, and for polyphonic, chordal textures. His pieces demand the familiar violinistic essentials – resonant tone, pure intonation, clear articulation – but feature linear shapes and chords requiring extraordinarily large left-hand stretches, unorthodox fingerings, quick leaps around the fingerboard, and adept string changes in both staccato and legato contexts. Shapey’s approach to writing for the violin recalls Leonard Meyer’s well-known description of him as a “radical traditionalist.” Shapey emulated the structures and motivic ideas of Beethoven, Brahms, and Haydn, while breaking away from tradition in his gestural and harmonic language. Similarly, he drew upon the techniques of traditional violin-playing, opening up new expressive possibilities of the player to extremes.

Shapey’s violin works are especially fascinating because of this intersection of his musical and communicative aims with his physical approach to the instrument. Though the technical puzzles he poses for the player are absorbing in themselves, those challenges are intrinsic to his expressive intentions. The huge intervals, leaps, and chords all contribute to what is probably the most pervasive characteristic of his music: its quality of expansiveness. Shapey wrote music with big dimensions – hefty, contrasting sections, dramatically wide-ranging melodies, and ruggedly distinct contours. At the same time, he exploited the physical characteristics of violin technique, with wide left-hand distances to be covered, and sometimes complex string crossings, in order to convey an expansive sense of space and time.

In all of the five works that I recorded, I observed a particular musical kernel that intriguingly relates to many of Shapey’s preoccupations, both expressive and technical: the dotted rhythm. This simple motive is featured prominently in all of these pieces, and indeed in much of Shapey’s oeuvre, with such frequency that it seems to have been something of an obsession for him. This makes sense when one notes that Shapey idolized Beethoven, and spoke often of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, Opus 133. The Grosse Fuge was performed by the Juilliard String Quartet at Shapey’s memorial service.[ii]

The Grosse Fuge, of course, presents remarkable ongoing strings of insistent, dotted rhythms. As Robert Carl relates, Shapey liked to tell people that he had spent a year studying Beethoven’s music, and that of Haydn, Mozart, and Brahms, in order to determine for himself the source of the strength of their compositions. He decided that this lies in the distinctiveness of their musical material, the almost tangible quality of their motives. Inspired by their example, Shapey described such concrete, compact musical ideas as “graven images,”[iii] or as musical “objects in space.”[iv]

In the Grosse Fuge, Beethoven used the dotted figure as a self-contained musical “object,” a building block that is the defining rhythmic element of the music, one with which he constructed whole passages and sections of the piece. The dotted rhythm possesses inherent musical traits that make it a vivid and intriguing compositional element with which to work. Its strongly articulated main beat makes it a firmly grounded pulse (whether or not the next beat is articulated or not), and its rhythmic components (long note plus short note) form an immediately recognizable shape. In contrast to the more horizontal directionality and constant motion of equal-valued notes, the dotted rhythm has a vertically weighted feel, and, in moderate to fast tempos, a natural jauntiness that denotes energy and liveliness. The rhythmic position of its shorter note can, however, affect the character of the motive in a variety of ways, depending on how it is played. It can rebound from the impetus of the main note, and pull briskly towards the next beat, propelling the motive forward, or creating momentum in a passage of continuous dotted rhythms. If purposefully delayed, it gives the figure a resistant and stubborn, or majestic and massive, character. If combined with intervallic leaps, the dotted rhythm possesses an extra measure of drama, conveying the sense of distances being crossed in a spurt of energy. Such leaps are a striking characteristic of the Grosse Fuge (see Fig. 1, mm. 30-31, or mm. 38-42), again suggesting that Shapey took inspiration from Beethoven’s work and seized upon its elements for his own creative purposes

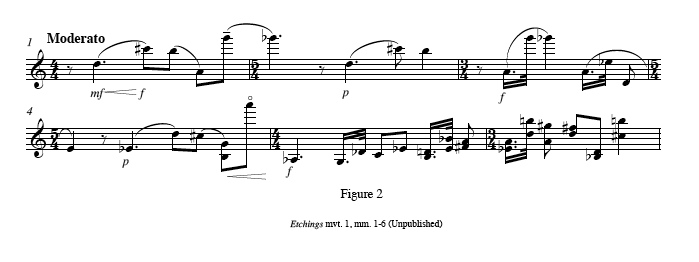

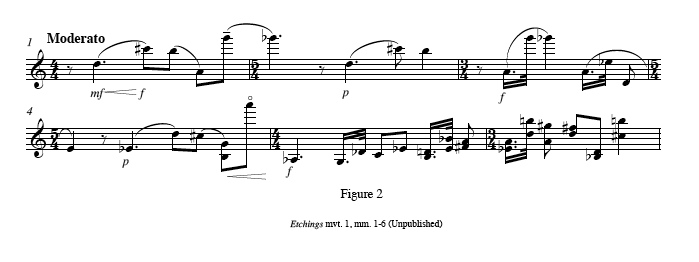

The dotted rhythm is prominent in the three faster movements of Shapey’s Etchings, an early solo work dedicated to Louis Persinger. The five short movements are variations of contrasting character. The piece is neoclassical in style, with frequently changing meters, and a spare monophonic texture that is sometimes enriched by double-stops. In this context, the dotted rhythm takes on an elegant, Classical, character. The “object” is tidily contained within the constraints of the meter’s pulse and its subdivisions. The rhythm appears frequently in the lively first movement, Moderato. It is first introduced in measure 3, incorporating a descending half-step motive introduced in mm. 1-2 (Fig. 2).

Shapey’s predilection for large leaps is already evident in the first bar’s wide-ranging intervals, the major seventh, D-C#, the major ninth, B-A, and the minor fourteenth, A-G. The expansive gestures of m.1 are restated in m. 3 in diminution, with the quick dotted rhythms enhancing the sense of acrobatic nimbleness.

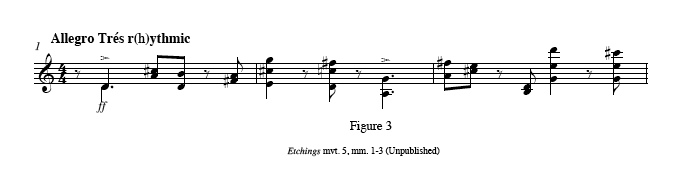

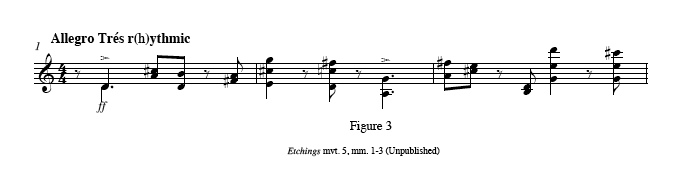

The third movement, titled Moderato vigoroso marciata, is primarily in 4/4. It is composed entirely of homophonic double-stops. Its many dotted rhythms are self-evidently march-like. The fifth movement, Allegro très rhythmic, is faster, and features syncopations and more irregular rhythmic patterns (Fig. 3).

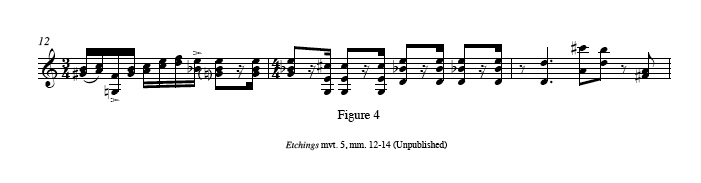

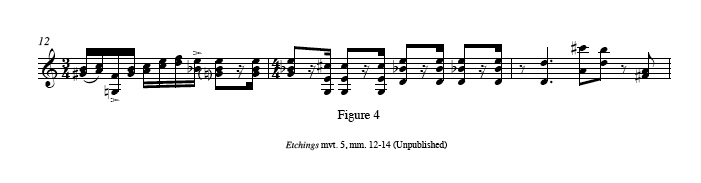

The rhythmic agitation of this movement causes the dotted rhythms to be more insistent in their forward motion. Their tendency to press onward to the next beat culminates in the triple stops in mm. 12-13 (Fig. 4). The last sixteenth note of m. 13 jumps into silence on the first downbeat of m. 14, toying with the expectations of the listener, as a syncopated beat arrives in place of the dotted rhythms of the previous measure.

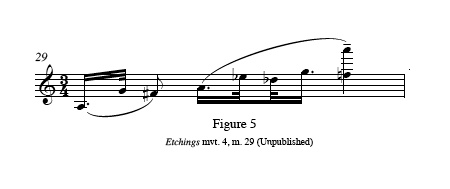

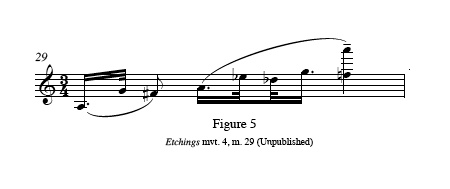

Overall, Etchings shows signs of Shapey’s interests in wide-ranging lines and chordal playing. However, aside from some large leaps, it does not pose the degree of technical challenge that he later explored. A hint of more complex technical problems occurs in m. 29 of the fourth movement, Andante cantabile, where a reversed dotted rhythm moves, legato, from a G to an F-A double-stopped tenth, a somewhat awkward move for the left hand to negotiate (Fig. 5). Perhaps Shapey reversed the rhythm to facilitate the movement of the hand. In any case, given the languid, lyrical mood of the passage, it seems musically appropriate to stretch the end of the beat, and ease into the double-stop. The high A emerges delicately and surprisingly as the G moves to the F underneath.

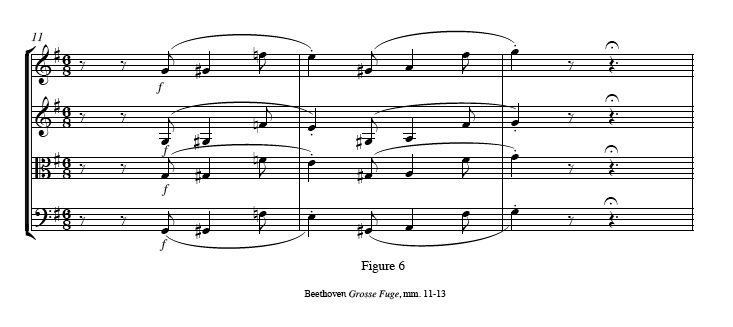

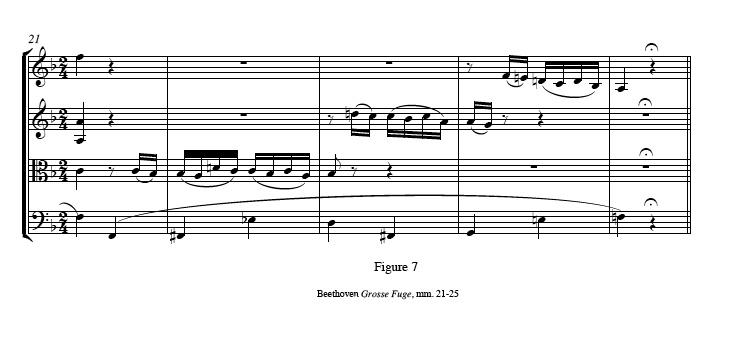

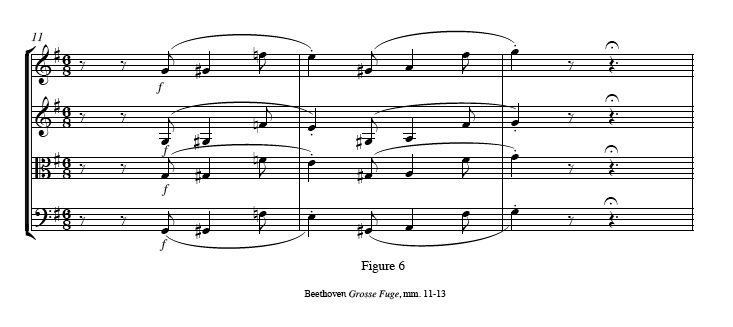

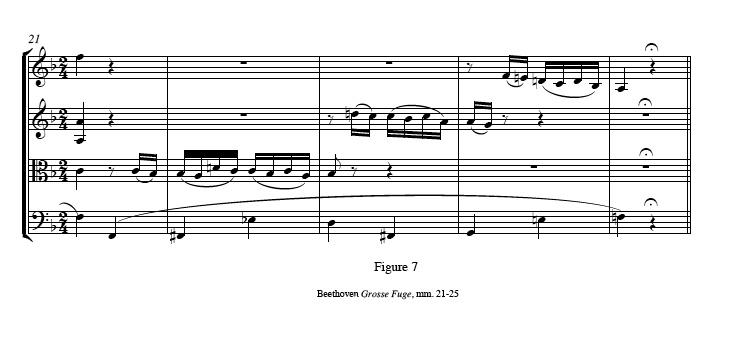

In Five, Shapey explored a rhythmic sense in which precise, firmly defined rhythmic ideas exist within a meter-less context, engendering a tension between precision and freedom. In this five-movement piece, Shapey worked with the dotted rhythm, extracting its essential gesture, and transforming it into various guises. This technique is somewhat reminiscent of Beethoven’s handling of the dotted-rhythm motive in the Grosse Fuge. Beethoven turns the motive into related forms. He employs ternary groupings of quarter notes and eighth notes (Fig. 6), and sixteenth note patterns in which the last of four sixteenths is the same pitch as the first of the subsequent group, suggesting a dotted rhythm (Fig. 7).

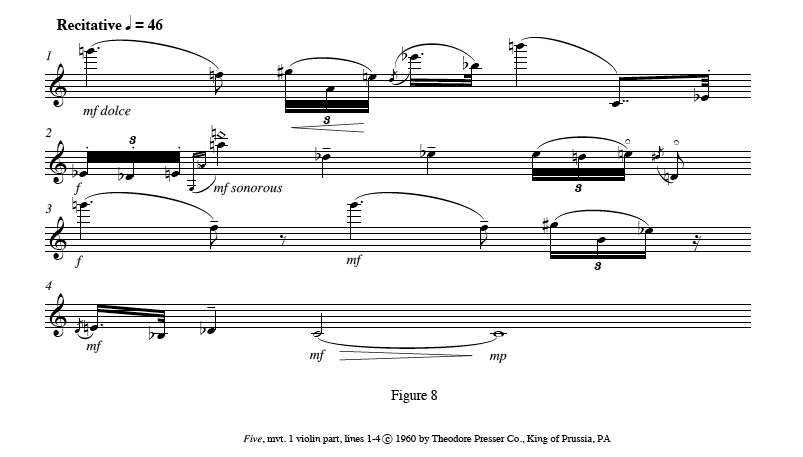

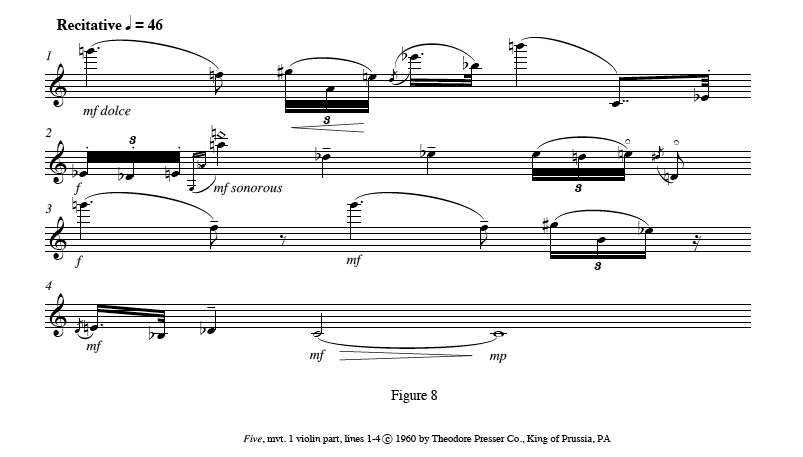

Rather than focus on the whole motive, Shapey concentrated on the upbeat gesture inherent in the dotted rhythm. In the opening Recitative movement of Five, the violin begins with a straightforward, broad dotted rhythm: a dotted quarter note plus an eighth note, in a tempo of quarter note=46. Shapey then presents several brief musical ideas in succession: a quick triplet, a single grace note, then an actual dotted rhythm. These all function as rapid upbeat gestures, each giving the effect of a dotted rhythm’s short note, leading into another event (Fig. 8).

Wide intervals abound: the opening G drops a major ninth to F, and the quick Eb–Bb dotted rhythm leads to a high B, requiring a fast left-hand shift. This pitch is a third higher than the opening G, producing a dramatic line of high peaks. A descent to the violin’s lower register brings about another series of “upbeat” gestures: a double-dotted rhythm, a triplet, and a two-note grace-note figure. These gestures lead to an A harmonic, the highest pitch so far.

Shapey employs these triplet and grace-note upbeat figures throughout the movement. Because of the absence of both meter and a regular pulse, the dotted rhythm gesture generates points of pronounced emphasis, and motion toward those points. The rhythm serves to create “objects” which exist in a free expanse of time. When strung together in a quick series, the gestures suggest both a repeated thrust toward a goal, and a certain awkwardness or struggle, comparable to climbing over a pile of rocks in order to reach a higher level.

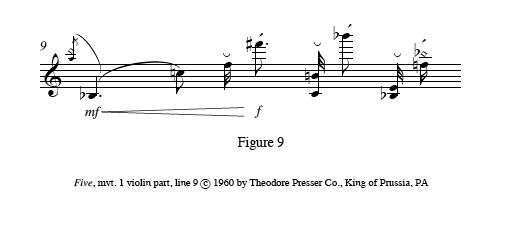

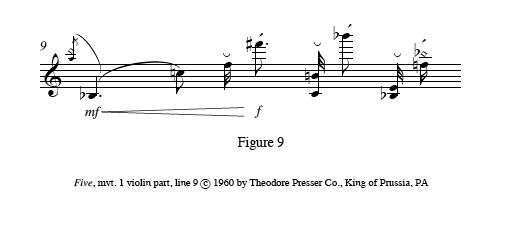

In evoking the dotted rhythm idea, Shapey often clarified his intention by writing symbols indicating “upbeat” and “downbeat,” a notation that he used in line 9 of Five (Fig. 9).

The sense of spaciousness created by this passage is especially dramatic, as the violin roams in an extended solo, untethered to the piano part. Shapey’s “downbeats” create an unsettling, jagged character. Shapey also uses the dotted rhythm as a conventional, emphatic closing gesture, as in line 4 (which is repeated at the end of the movement ) (Fig. 8).

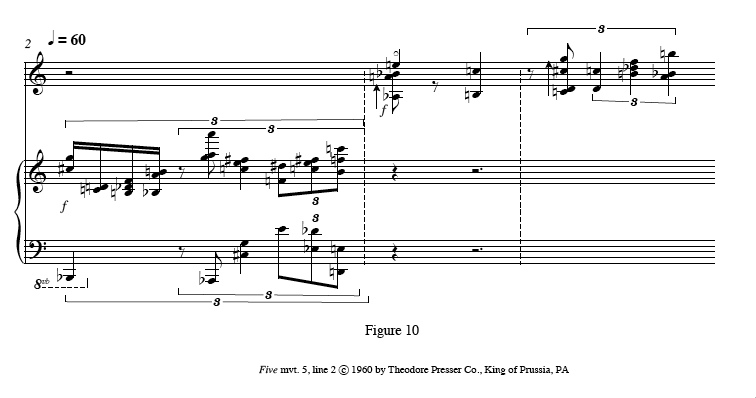

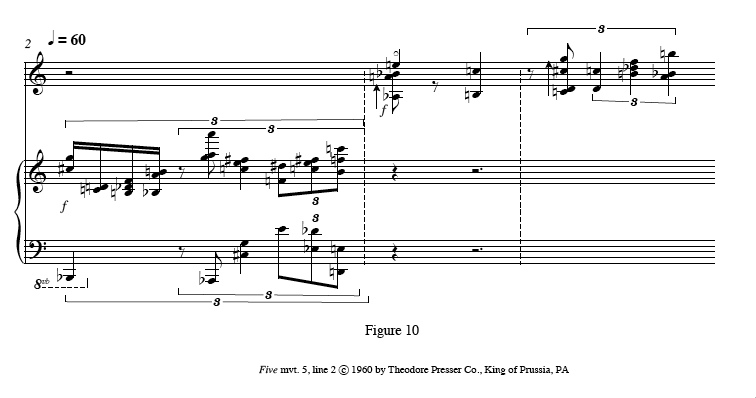

Dotted rhythms do not play much of a role in the rest of Five. However, the last movement contains one other transformation of this rhythm that can be seen in Shapey’s other works: chords. Chordal playing on stringed instruments usually necessitates that the notes be somewhat arpeggiated, because the bow must traverse the curve of the bridge as it contacts the strings. This causes a grace-note-like effect that can also be interpreted as a kind of dotted rhythm, depending on how the “upbeat” notes are articulated or lengthened. Shapey maximized this effect by writing chords involving not only all four strings, but also large intervals, and left-hand positions requiring unusual extensions and knotty fingerings. Consequently, there is an added measure of time and effort involved in crossing from one side of a chord to the other. He also often included dissonant, clashing intervals within the chord, creating timbral tension. For example, the first violin chord of the fifth movement is Ab-A-Bb-E. This requires a moderate stretch from Ab to A, plus a movement of the first finger from the Ab on the G string over to the Bb on the A string, necessitating an arpeggiation. The minor second, A-Bb, and the tritone, Bb-E, inject jolts of dissonance, which lead into the sound of the bright, sustained open E string (Fig. 10)

In the next “bar” (Shapey used dotted bar lines here), B-Db-F is an especially awkward chord, which I choose to play by shifting from a double-stop in second position (B-Db) to one in first position (Db-F). This splitting of the chord into two components creates an aural result similar to that produced by the broken chords around it, and is in keeping with the heavy, laborious character of the passage.

The various dotted rhythm gestures seen in Five are plentiful in Shapey’s Partita, written five years later. Like Five, this three-movement solo work features a great deal of chordal writing, involving complex, tangled fingerings and wide intervals. The intervals are often dissonant, so it is important to use sweeping arm movements to draw rich sound from the strings, so that the pitches resonate and can be heard clearly. The frequent splitting or arpeggiating of the piece’s numerous chords contributes to the craggy robustness of the music.

In addition to chords, Shapey makes much use in the Partita of quick upbeat triplets, and also employs his upbeat and downbeat symbols. As in Five, these symbols serve a meaningful purpose, for the rhythmic emphasis can be ambiguous unless elucidated by the player. There are no bar lines in the first two movements, so the rhythmic values and patterns are irregular and the main emphases come at unpredictable moments.

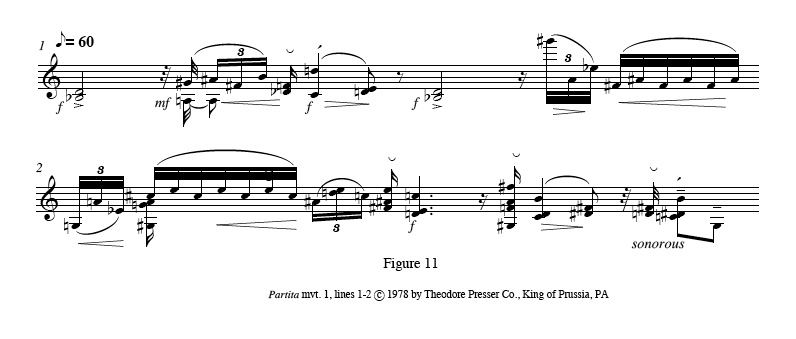

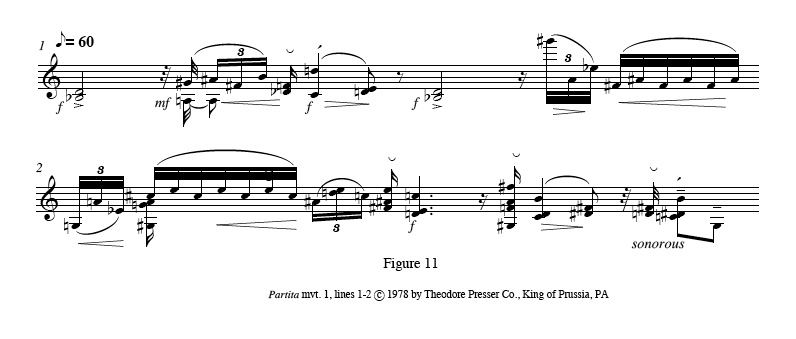

In the first movement, a theme and five variations, melodic and rhythmic units recur in modified forms, or are rearranged in different orders. In the opening sections, the ideas are grouped into fragments. The music progresses in compact, declamatory bursts. Long, sonorous tones are often preceded by sixteenth notes, on which Shapey placed upbeat symbols. The upbeats are usually double-stopped or chordal, requiring firm bow articulation (Fig. 11).

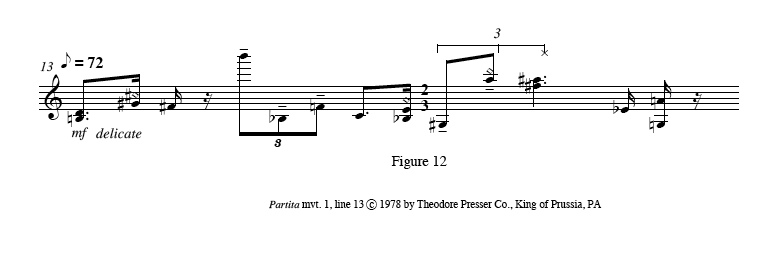

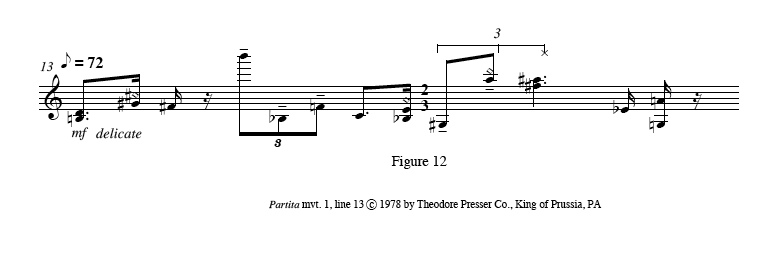

The beginning of the scherzando third variation presents a more continuous line, which jumps delicately across wide intervals. In this variation, the dotted rhythm is one of several small rhythmic cells that are strung together horizontally, including triplets, parts of triplets, and single eighth notes. As the various motives alternate, there is little sense of any beat or pulse, and the dotted rhythm becomes less distinct as a recognizable “object,” its components now forming part of a disjointed rhythmic line (Fig. 12).

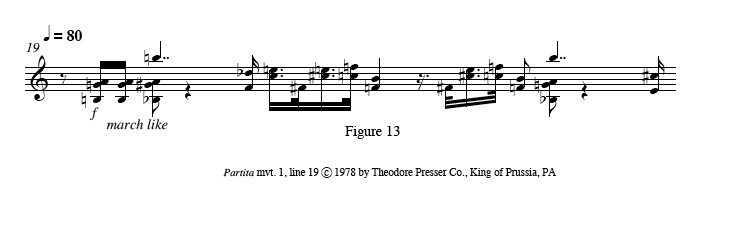

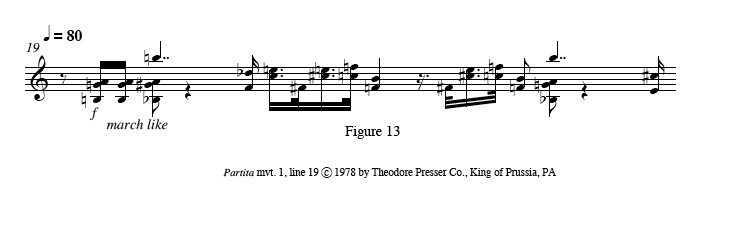

The fourth variation is labeled “march-like.” Its dotted rhythms move twice as fast as those in the preceding sections (FigEx. 13). Mostly double-stopped, these rhythms require clean attacks to project their crispness. The variation also includes weighty four-note chords, involving awkward left-hand fingerings. The effort entailed in breaking the chords clearly is again an important factor in conveying the expressiveness of the music.

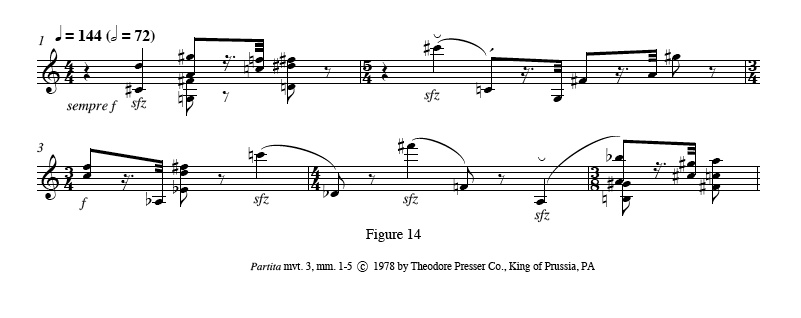

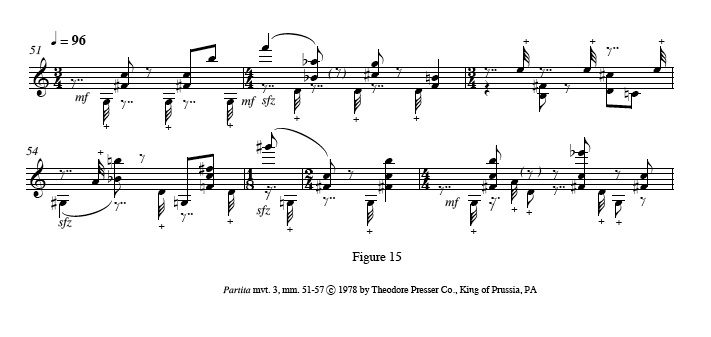

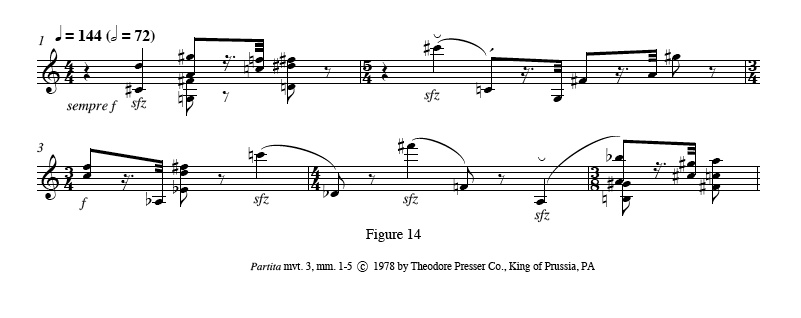

The third movement of the Partita consists of a Grosse Fuge-like series of dotted rhythms. In this case, the rhythms are actually double-dotted, a characteristic which imparts an especially jaunty springiness to the music. The dotted-rhythm “objects” are grouped into short phrases that usually open with a quarter note or eighth note sforzando upbeat. These sforzando attacks (marked with an upbeat symbol at their first few appearances) are basically an exaggeration and elongation of the upbeat idea. Their weighty gravitational pull counterbalances the airborne lightness and clipped quality of the thirty-second note in the double-dotted rhythms (Fig. 14).

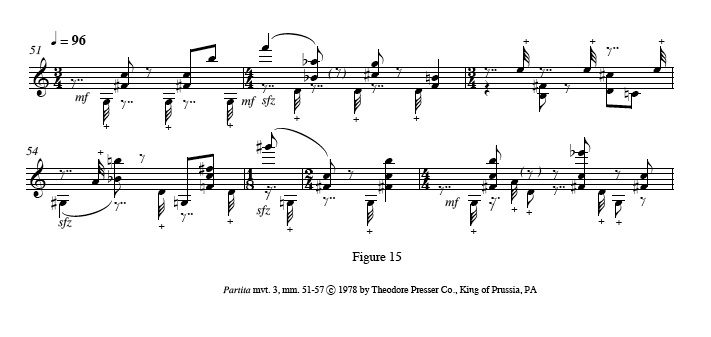

In the movement’s middle section, beginning in m. 51, Shapey turned the double-dotted rhythm into a witty and technically tricky figure. He transformed the upbeat thirty-second note into a left-hand pizzicato, which leads in most instances to a bowed double-stop. The pizzicati are played on open strings, facilitating their execution and requiring clean and quick moves from pizzicato to arco (Fig. 15).

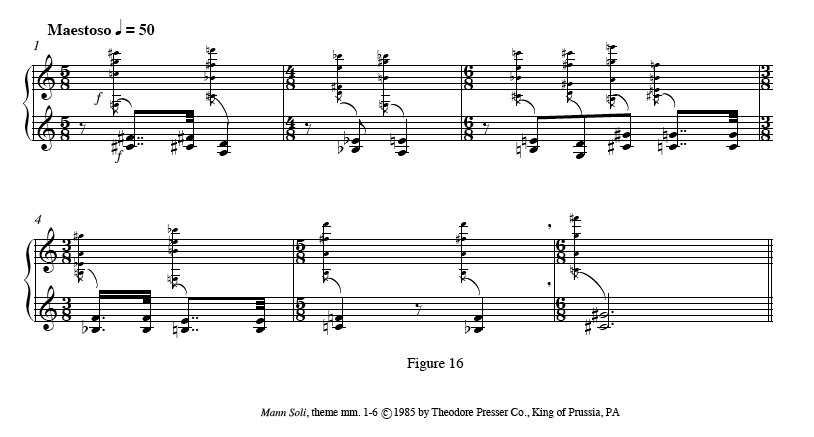

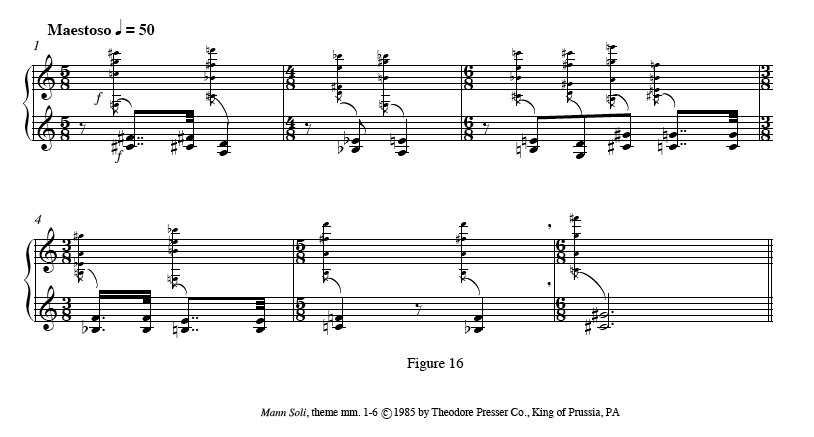

Mann Soli is composed of a theme and five variations, the theme returning at the end of the piece. The dotted rhythm is a central element of the material. The maestoso theme is written across two staves, the lower staff with the primary rhythm and pitches, while four-stringed grace-note chords are placed on the upper staff. (Fig. 16). The lower staff’s “melody” is in double-stopped fourths or fifths, and moves at a steady pace. Grouped into a few short phrases, it features weighty, double-dotted rhythms in the first measure and mm. 3-4. This powerful, declamatory line serves as a rhythmic foundation for the grace-note chords attached to it. Massive and very intense, with their wide intervallic range, strikingly dissonant intervals, and bright topmost notes on the E string, these chords must be split into two double-stops, essentially forming two-note grace-note figures. They repeatedly deliver huge upbeat motions that land forcefully on the subsequent beats of the theme. When combined with the main line’s own dotted rhythms, they produce a series of three upbeat articulations, fired off in a row with jarring intensity.

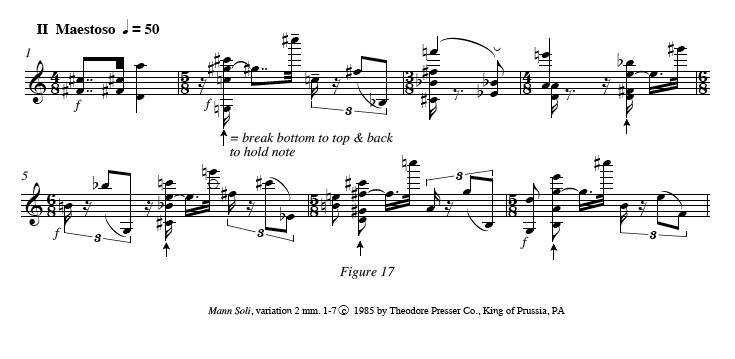

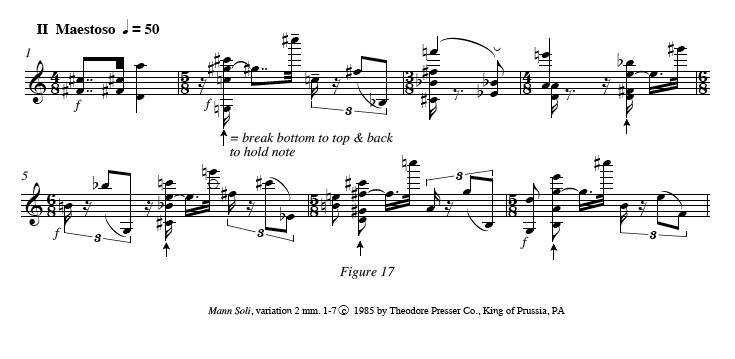

The first variation incorporates the dotted rhythm simply, with a single dotted figure opening each phrase. In the second variation, Shapey again employs the double-dotted rhythm, as he turns the theme into a primarily monophonic line that jumps around across an enormous pitch range (Fig. 17). The violin writing includes many vaulting left-hand leaps. Elaborate four-note chords punctuate many of the variation’s longer sustained notes. These chords directly recall the grace-note chords in the main theme, both in their intervallic make-up, and in the rhythmic effect of their arpeggiation. Shapey ties the second-highest pitch in each chord into the following held note, and writes, “break bottom to top & back to hold note,” along with a symbol that combines two arrows, one pointing upward, the other curving back downward. This kind of bi-directional arpeggiation is an established technique among string players, and is sometimes used in polyphonic works, such as the solo sonatas of Bach, in order to bring out specific inner lines. Shapey’s employment of the device serves that purpose, while replicating the swooping motion of the opening theme’s grace-note chords, which break upward in two double-stops, then veer back downward to arrive on the main notes.

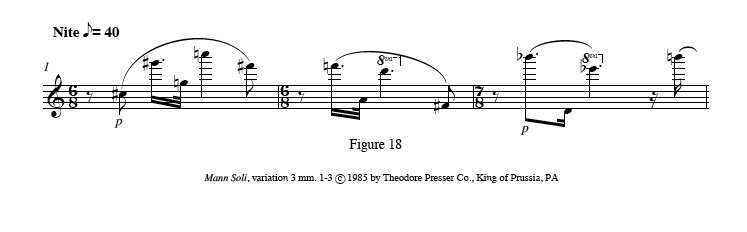

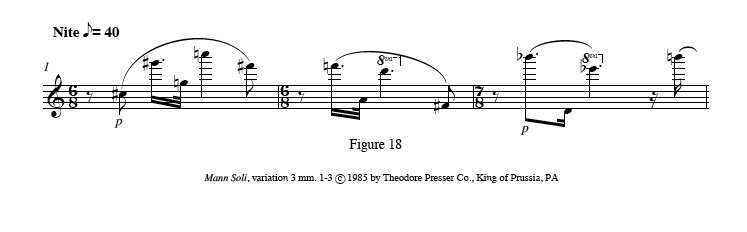

In variation 3, dotted rhythms appear as part of a legato melodic line that moves by large intervals between the violin’s middle and high registers (Fig. 18). Quiet and spare, the variation conveys a remarkable sense of vast expanses of space and time. While the melody is essentially slow-moving, the dotted rhythms gently nudge it forward, with quick motions toward the subsequent beats. The large leaps in the dotted rhythm figures suggest a tightrope walker, making exquisitely graceful leaps above an open expanse.

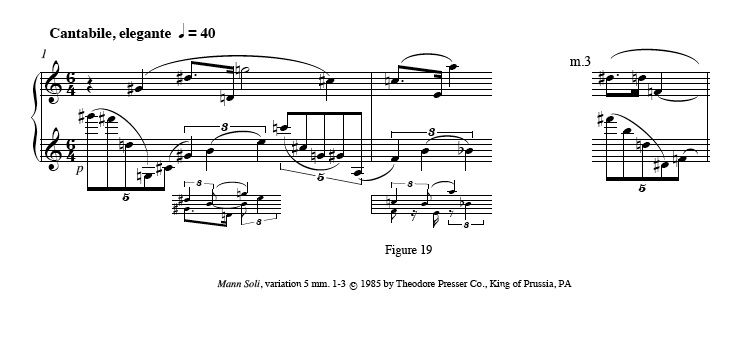

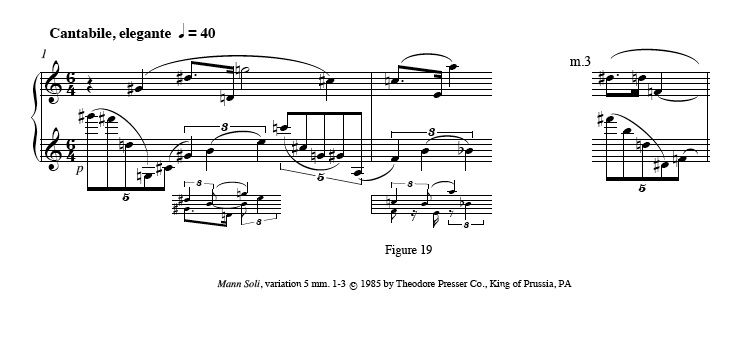

The fourth variation is based entirely on dotted rhythms, bunched in brief phrases that halt on double- or triple-stopped chords, played on strong beats. In the fifth variation, the dotted rhythm is subsumed into a contrapuntal, polyrhythmic texture in which two cantabile melodies, written on separate staves, are played simultaneously. The two lines are closely entwined, crossing each other registrally, and interlacing disparate rhythms. The dotted rhythm is combined with large leaps, forming graceful, Romantic gestures, and leading the long, meandering phrases toward points of expressive focus (Fig. 19).

Since it is technically impossible to play both melodies at once, one must foster this illusion by seamlessly alternating between the voices and employing unusual fingerings. Shapey provides little clue as to how to execute the passage. There are various possible solutions, depending on which tones one chooses to sustain or drop. In m. 1, I play the two lines simultaneously by momentarily dropping the D# on the A string to play the B with the first finger. The B is then double-stopped with the open D string, and with the G on the E string. In this way, the dotted-rhythm leap is traversed, while both lines are continuously sustained. In m. 2, I choose to drop the lower line at the leap. Leaving the B-E fifth that occurs on the last sixteenth note of beat 1, I shift to fourth position for the A, playing it alone before bringing in the B flat on the D string on the second triplet of that beat. This allows for a smooth technical transition, and also creates a moment of open space in which the A sings through.

In this variation, the dotted rhythm is sometimes a passing element in the fluid texture of the music, rather than a focal point. In m. 3, it is placed against an eighth note quintuplet. The two lines are briefly entangled, then unspool, as the dotted rhythm occurs simultaneously with the quintuplet. At the point where the two rhythms intersect, the lines share a common pitch, D natural, which ties them together momentarily, and obfuscates the rhythmic distinction of the dotted figure (Fig. 19).

I play the upper-line D with the first finger, combining it as a unison with the lower-line D, played with the fourth finger on the D string. The fourth finger is then double-stopped with the F, played with the third finger on the G string. In order to sustain both lines, I shift to second position, moving the F to the first finger on the D string. The D# and F in the quintuplet are played on the G string.

Whereas Shapey’s music of the 1960s-80s is freely gestural and fragmented, his late works show a return to long lines and a strong metrical pulse, with simple rhythmic ideas interlocking in a dense web. Millenium Designs, for violin and piano, presents swathes of neatly meshed counterpoint, in which rhythm and texture are more important than melody. Formed of sections that recur in different movements, the piece is a large-scale patchwork of shifting characters. The dotted rhythm is very prevalent in this piece. It bears traits of both the weighty upbeat gestures of his middle-period music, and the Classical elegance of his early pieces.

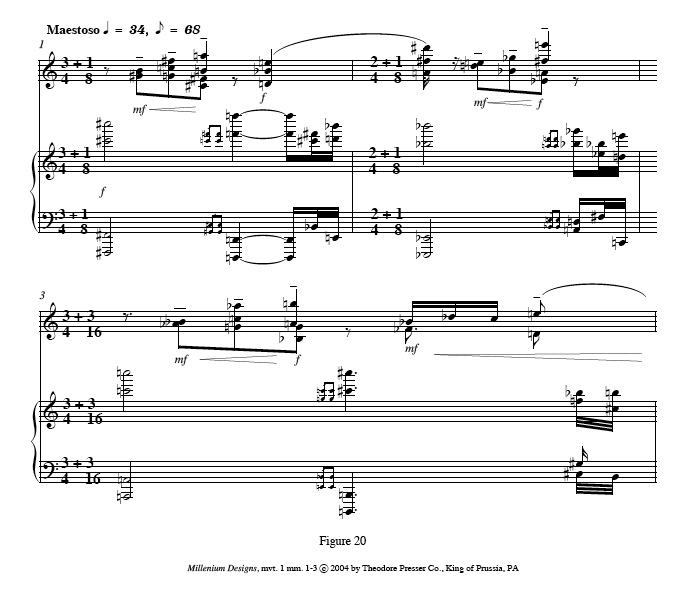

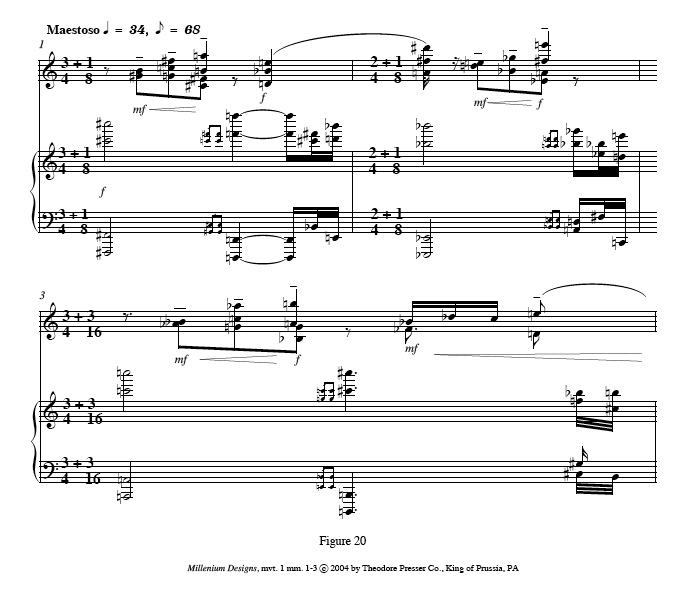

The opening is a mighty refrain that returns both at the end of the movement and the end of the work. The instruments establish a slow eighth-note pulse as they alternately play heavy chords. The dotted rhythm is present by virtue of the violin’s splitting of the chords, which pushes the motion onward, while also evoking a sense of labor and struggle. In the violin’s repeated gesture of three eighth notes, Shapey increases the effect of the crescendo by making the last of the three a four-note chord, typically involving dissonant intervals and awkward fingerings. The piano’s chords are insistent, with upbeat gestures comprised of pairs of either grace notes or thirty-second notes (Fig. 20).

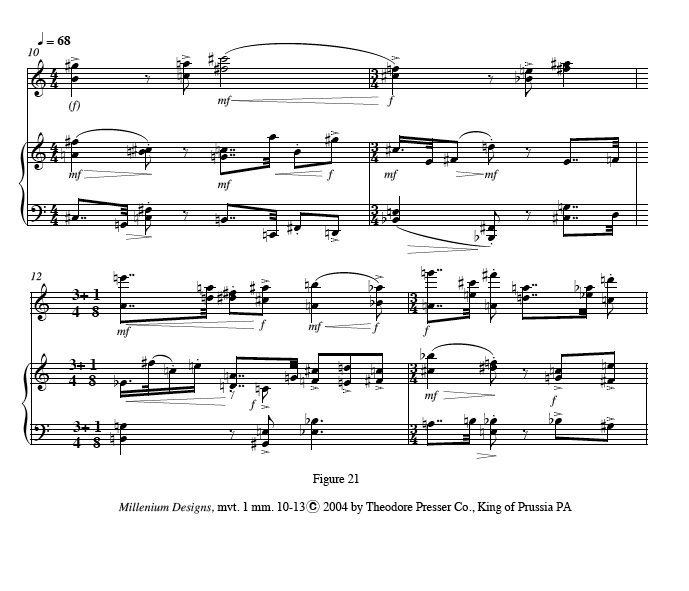

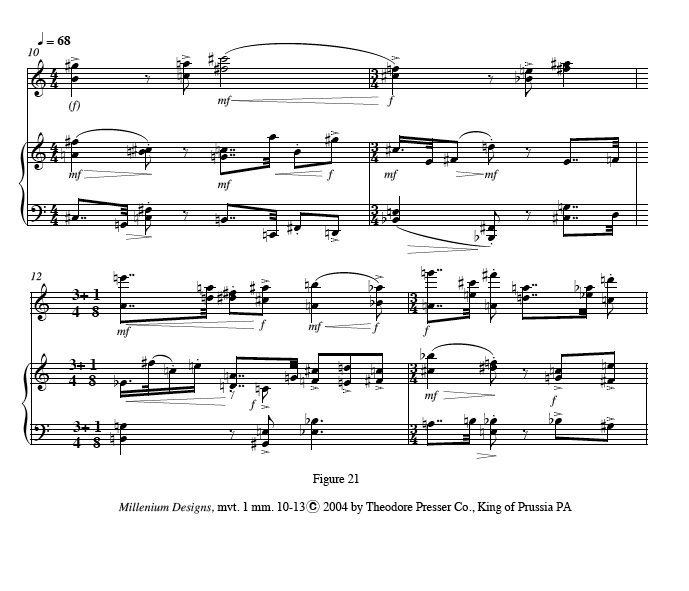

In much of the rest of the piece, the dotted rhythm is tightly locked within an eighth-note-based framework. The squareness of the rhythmic cells and neatness of the “objects” harks back to the neoclassical character of Etchings. In Millenium Designs, the dotted rhythm suggests certain emotional traits. In sections of moderate tempo, such as m. 10 in the first movement (Fig. 21), it creates a gentle tension, as the listener waits momentarily for the arrival of the next note. Shapey sometimes enhances this effect by double-dotting.

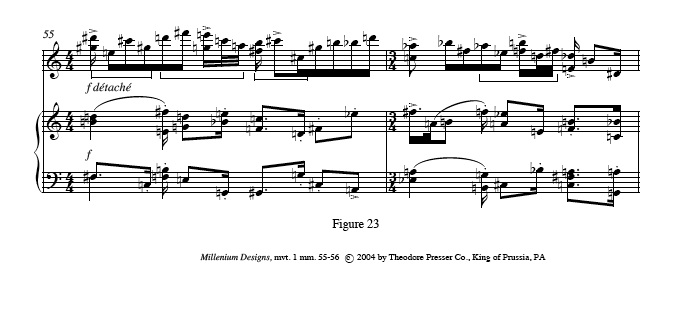

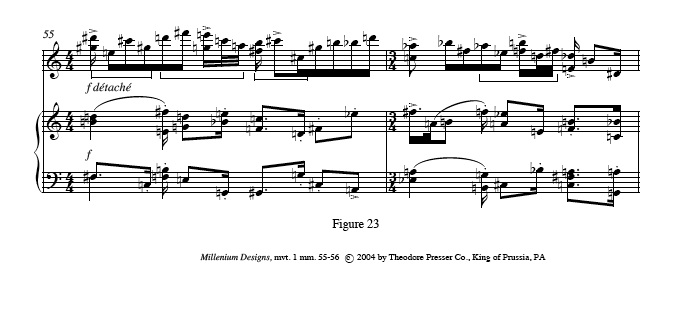

In faster sections (Fig. 22), the dotted rhythm has a jaunty character, conveying a more vertical stress, even as the music proceeds in a linear fashion. This jauntiness contrasts with the firmness and swagger of the section beginning at m. 55, where the violin plays groups of notes of equal value (Fig. 23).

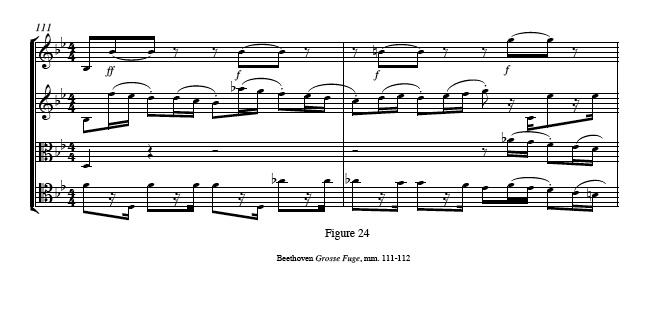

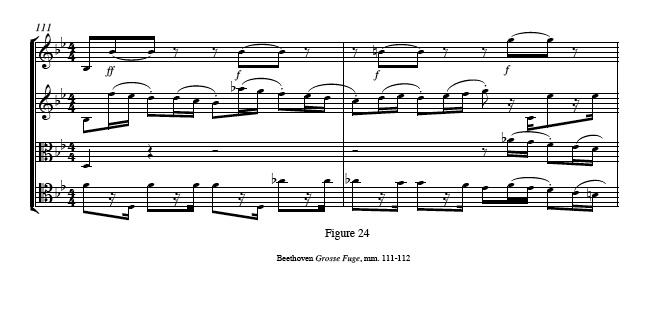

Shapey’s manner of interlocking the dotted rhythm with other rhythmic units can be likened to Beethoven’s procedure in passages of the Grosse Fuge. At m. 111, the dotted rhythm is played by the cello, landing on the beginning of each beat of the 4/4 bar (Fig. 24). It is combined with the second violin’s repeated anapestic figure of two sixteenth notes leading to an eighth note, and with the first violin’s cross accents on the second half of beats 1 and 3. This layering of rhythms creates a texture in which one hears several discrete lines simultaneously, with emphases occurring one after the other in quick succession.

Beethoven was clearly the main exemplar of Shapey’s musical ideals. Even more than Haydn, Mozart, or Bach, Beethoven invested the individual motive with charged expressive significance, giving his music the etched impact of a “graven image.” The powerful character of Shapey’s music, whether rugged and bold, or ethereal and lyrical, is especially close in spirit to that of Beethoven. Furthermore, Shapey’s idea of virtuosity seems particularly akin to Beethoven’s. Although both composers sometimes brought agile brilliance to the fore, they often embraced a sense of physical exertion, making it an expression of strength in their music. Beethoven’s music sometimes appears blatantly to disregard the norms of idiomatic instrumental writing, aiming instead for a purely musical objective. His works can be very unidiomatic for stringed instruments, using patterns often more suited to the piano. With his knowledge of the violin, Shapey worked to push the performer to the extremes of established technique, designing technical challenges to convey the toughness, strenuousness, and spaciously dramatic qualities of his music. In this way, his pieces achieve the near-tangibility of their musical ideas through the physicality of their execution, and they expand the range of expression that virtuosity can supply.

1 Music by Ralph Shapey, Centaur CRC 2900. Miranda Cuckson, violin, Blair McMillen, piano.

[i] Robert Mann, interview by author, New York, 4 September 2007.

[ii] Anthony Tommasini, “Music; Rugged Music Once Packaged in Plain Brown,” The New York Times, 10 November 2002.

[iii] Robert Carl, CD liner notes, Ralph Shapey: Radical Traditionalism, New World Records 80681-2.

[iv] Cole Gagne and Tracy Caras, Soundpieces: interviews with American composers (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1982),

“Világ” is a Hungarian word meaning “world” or “illumination”.

“Világ” is a Hungarian word meaning “world” or “illumination”.